At an Ancient Site, Holding Hands across History

A rock shelter in Oregon tells a story of human habitation thousands of years earlier than previously thought

By Lexie Briggs and Laurel Hamers • October 4, 2023

8 min readThe Rimrock Draw rock shelter doesn’t look like the kind of place that could upend our understanding of human history in North America.

The basalt overhang near Burns in Eastern Oregon sits unassumingly on a dusty plain crisscrossed by dirt roads and sprinkled with dried-up lake beds. Looking out across the high desert landscape—one of the least populated parts of Oregon—one sees sagebrush in every direction.

But recent archaeological finds have thrust the remote site into the spotlight. A collection of stone tools interspersed with tooth enamel from extinct mammals suggests that humans lived here eighteen thousand years ago—several thousand years earlier than previously thought. That makes Rimrock Draw the earliest currently known site of human habitation in North America.

The discovery challenges longstanding assumptions about when and how humans reached North America. It also confirms what Indigenous people have said for years—that their ancestors have lived here since time immemorial.

The finds tell an unfolding story about climate, too. Archaeological and geological evidence describe a landscape that has undergone dramatic transformations in the span of human history, shifting the way people used the land. And it’s still changing today.

Patrick O’Grady, an archaeologist with the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, is excavating the site in collaboration with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Almost every summer since 2012, O’Grady, of the College of Arts and Sciences, has brought students to Rimrock Draw for a six-week archaeology field school. Slowly, they’ve dug into the past, carefully probing layers of dirt for clues to how people have interacted with this land over millennia.

O’Grady, BS ’96, MS ’99, PhD ’06 (anthropology), has been keeping the fact that this could be the oldest known human site in North America under wraps for nearly ten years. Now, with additional confirmation from more artifacts and new techniques, he can finally talk about it. Says O’Grady: “These are now dates we can believe in.”

Old, older, oldest

The Rimrock Draw find was made possible by geography and a bit of luck. The rock shelter faces north. Because of prevailing winds, layers of sediment have built up over time, preserving a rich trove of artifacts and evidence of human habitation stretching back thousands of years in layers of dirt that act as a geological timeline. In an undisturbed setting, the deeper something is buried in the strata, the older it is.

O’Grady began investigating Rimrock Draw in 2011, after BLM archaeologist Scott Thomas noticed tall sagebrush and dark, charcoal-speckled deposits against the rock wall. These were clues that deep, rich sediments with evidence of ancient cooking fires might be preserved there, and that a dry stream channel was once a reliable source of water.

The first indication that the site was special came in 2012, when O’Grady’s team found a tool under a layer of volcanic ash. Roughly palm-sized, it’s made of a honey-gold agate, with three working edges. One edge is straight and sharp and was possibly used for cutting; another is convex and ideally configured for skinning. A third has a serrated edge worn with use. Testing of the tool revealed traces of bison blood along its edges.

Initially, the team thought that the volcanic ash, or tephra, above the tool came from the eruption of Mount Mazama, which formed Crater Lake more than seven thousand years ago.

But when BLM officials submitted the ash for identification, they got a surprise. Emeritus Professor Franklin Foit of Washington State University found that the tephra was instead from an eruption of Mount St. Helens fifteen thousand years ago. This suggested that the tool underneath must have been made before then—far earlier than scientists had thought people were in the area.

If true, the discovery would upend the understanding of the earliest human habitation in North America, O’Grady’s team realized. At the time of their original excavation in 2011, the oldest known site was Paisley Caves in south-central Oregon, which had human habitation dating back fourteen thousand years. The Rimrock Draw site had the potential to be much older. But they needed more evidence.

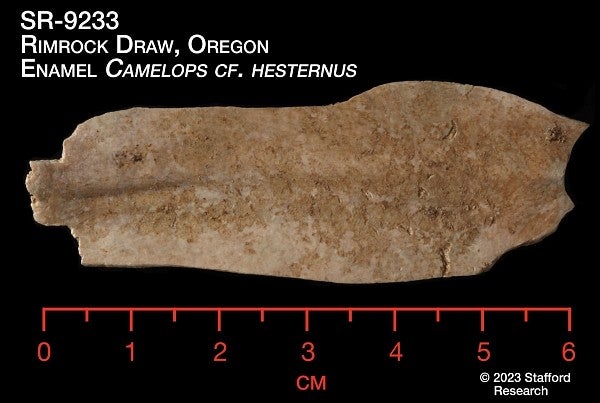

Fortunately, another find nearby in 2012 provided backup: the team unearthed a concentration of large herbivore tooth enamel fragments, some so large they could cover a palm, underneath the layer of volcanic ash and above the stone tool. Edward Davis, associate professor of earth sciences and director of the UO Condon Fossil Collection, helped O’Grady identify the genus Camelops. It was most likely Camelops hesteronius, or “yesterday’s camel,” which went extinct about eleven thousand years ago.

But how old were the tooth fragments really? O’Grady called in Thomas W. Stafford, Jr., a geochemist in New Mexico who specializes in radiocarbon dating, to test the tooth enamel. Stafford found the camel tooth enamel was more than eighteen thousand years old. And because the agate tool was found buried deeper than the tooth enamel, its makers must have visited Rimrock Draw even earlier.

With finds that would set the date of human occupation of North America two thousand years earlier than previously established, you need to be sure, O’Grady says. It took three more years in the midst of a pandemic to resample and retest the enamel. This spring, the team finally got confirmation: the numbers held. More than eighteen thousand years ago, humans lived at Rimrock Draw.

This timeline fits with Indigenous oral histories of life on the land, says David Lewis, BA ’97 (humanities), MA ’00, PhD ’09 (anthropology), a professor of anthropology at Oregon State University. Many tribes have stories of the Missoula Floods, volcanic eruptions, and other geological events from the period.

“Tribes also have oral histories of encountering giant animals, monsters on the land,” he says. “Rimrock Draw rock shelter’s evidence suggests that we did interact with the megafauna, and they may have become characters in our histories of the time before memory.”

The agate tool was no longer just a beautiful connection to people who lived in the area a few millennia ago. It was the earliest evidence of Indigenous people in North America identified to date.

A tale of climate and landscape

Pushing back the date when people inhabited this area raises questions about how they got here and what the landscape looked like.

Today, the shadow of these basalt cliffs would be a harsh place to call home. Less than ten inches of rain falls per year and the few water sources are seasonal. Wind often whips dust across the open and empty landscape. Despite these unaccommodating conditions, the Wadatika band of Northern Paiutes, now known as the Burns Paiute Tribe, lived in the region until they were forcibly removed in 1878. Today, about seven thousand people live in what is now Harney County, including more than 140 members of the Burns Paiute tribe, spread over more than ten thousand square miles.

But eighteen thousand years ago, this was a cooler and wetter environment. A stream once ran near the rock shelter, its path recorded in layers of dirt. In place of the mostly dry lake beds that dot the area today, O’Grady thinks a nearby basin was once a large lake. A community might have gathered on its shores, harvesting plants recovered from the rock shelter such as wada and wapato. At some point, these water sources shrank and dried up, changing the way people lived on the land.

“The real story is what we learn about the environment. As the environment changes, people’s response to it changes.”

For many years, archaeologists trying to piece together how people arrived in North America championed the land bridge hypothesis—the idea that, as the Ice Age ended and glaciers retreated, people migrated from Asia into North America via an ice-free corridor, known as the Bering Land Bridge, eleven thousand to sixteen thousand years ago. The land bridge stretched between present-day Alaska and Russia. From there, people dispersed across North America, gradually making their way south.

But the Rimrock Draw finding is part of a growing body of evidence suggesting a more complicated story. Given the find by O’Grady’s team that people were living in Oregon more than eighteen thousand years ago, it’s likely that the first people arrived in North America more than twenty thousand years ago. At that time, the climate was much colder and the land bridge would have been impassable. People could have arrived by boat during summers—an idea known as the “kelp highway,” hypothesized by scientists including the UO’s Jon Erlandson, professor emeritus of anthropology. But during winters, seas would have been frozen, making passage difficult.

“This research, along with the work of other museum archaeologists and collaborators, demonstrates that Indigenous communities were in Oregon and the Americas far longer and their migrations were much more complex than once believed,” says Todd Braje, director of the Museum of Natural and Cultural History. “Patrick O’Grady’s work is helping rewrite scientific paradigms about the peopling of the Americas and the Indigenous histories of our state, highlighting Native Oregon histories that date back into the deep Pleistocene and suggesting that their migrations followed routes both on land and at sea.”

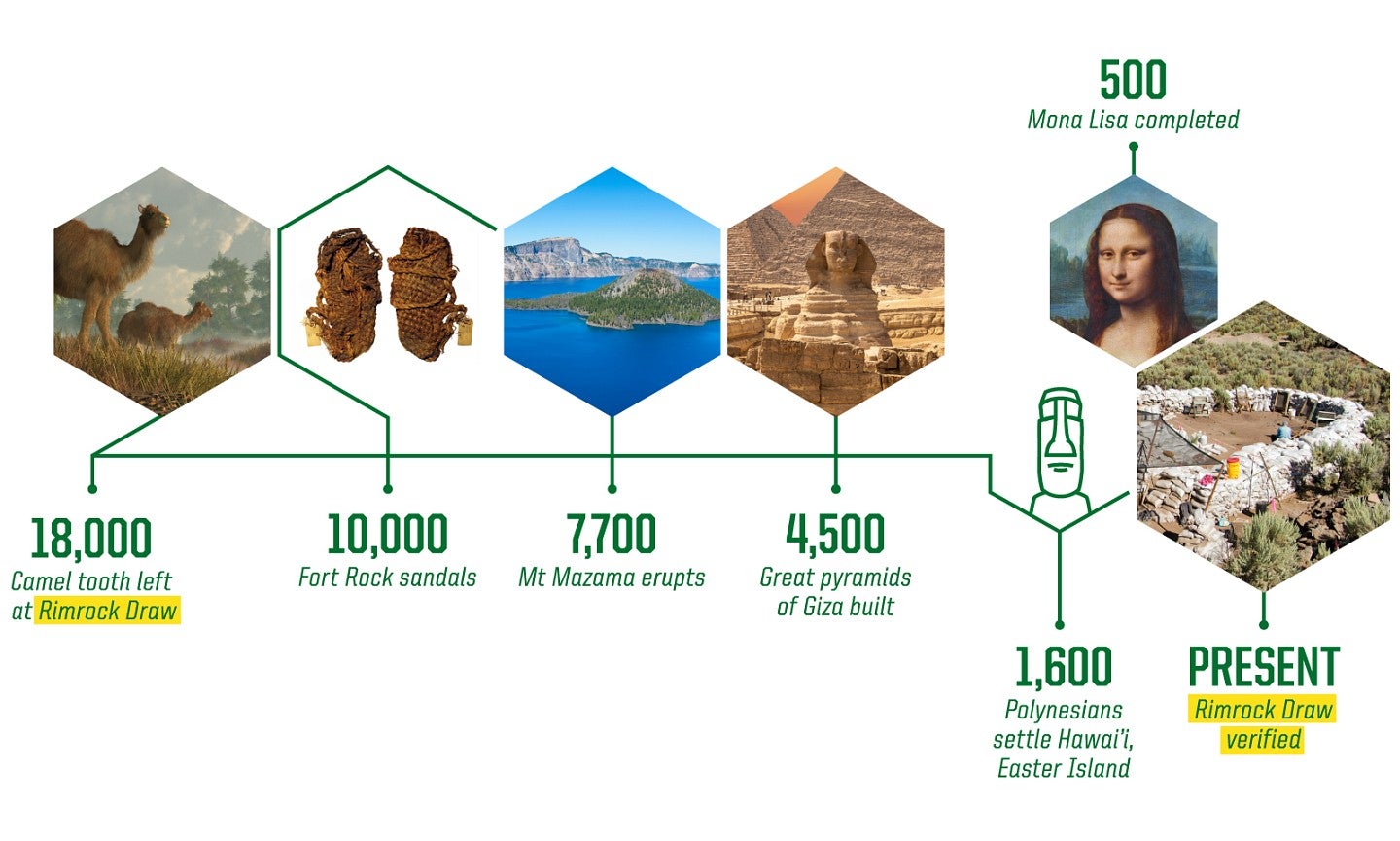

How Many Years Ago?

Geologically speaking, a tooth from eighteen thousand years ago old isn’t all that old. But within the context of human history, the Rimrock Draw settlement was in the deep, deep past.

Years approximate. Timeline graphic by Kyla Tom, University Communications; research by Jered Benedick, UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

The evolving story reflects the way that climate and human presence are inextricably linked. O’Grady’s goal as an archaeologist—and the lesson he imparts to his students—isn’t just to find artifacts. It’s to understand how people were interacting with and using the land on which they lived.

It’s clear that this landscape looked different eighteen thousand years ago and ten thousand years ago. And it’ll look different a thousand years from now, too.

This year, students at field school got a clear reminder that climate change is present and ongoing: smoke from nearby wildfires blew in, interrupting their work for a week. Some students worked in N95 masks to avoid breathing smoke. Others went home until the air cleared.

“The real story is what we learn about the environment,” O’Grady says. “As the environment changes, people’s response to it changes.”

Though O’Grady has spent many nights camping near Rimrock Draw, he never tires of snapping photos of the sunset over the sagebrush plains. Dusk brings welcome relief from the blazing sun after a hard day of fieldwork, casting long shadows and painting the wide-open sky pink and orange. It’s when animals come out, too, and the high desert comes to life, revealing a side that’s hidden during the day.

The lushness of evening evokes the landscape that was here many millennia ago, and the connection to the past seems closer than ever.

Whenever someone finds a tool at field school, O’Grady reminds them to think of the last person who held it thousands of years earlier. Through these artifacts, he says, “we’re holding hands across history.”

Lexie Briggs is a marketing and communications specialist for the UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

Laurel Hamers is a senior writer and editor of science and research communications for University Communications.

Rimrock Draw lead photo courtesy Bureau of Land Management.