Mystery Canvas Ties Famed Painter Motherwell to UO Days

Physics professor and art expert Richard Taylor recounts the story of “a true great of American art” who taught briefly at the UO

By Richard Taylor • Image © 2021 Dedalus Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY • April 6, 2022

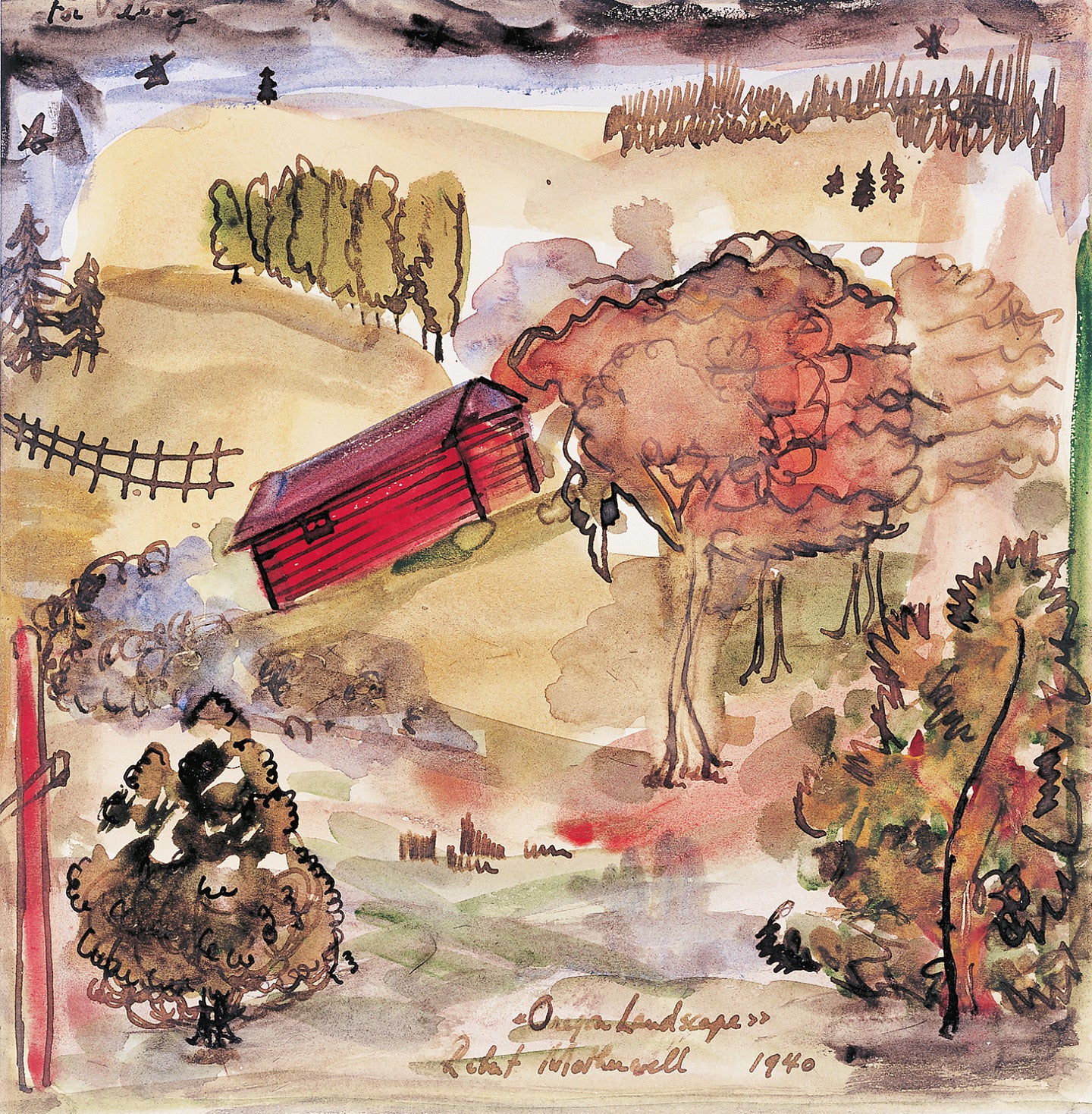

5 min readHolidaying in Guernsey several years ago, I scrambled along the rugged coastline to the sites that Pierre Renoir committed to canvas 140 years earlier. Enjoying the thrill of seeing his sun-drenched seascapes with my own eyes, my mind wandered back to Eugene. Had the natural beauty of Oregon inspired any celebrated artists? Some might speculate that hippy-dippy Eugene’s greatest art legacy is the tie-dyed T-shirt or perhaps the Animal House movie. But they’d be wrong. Robert Motherwell, one of the true greats of American art, taught at the University of Oregon during 1939-1940. Yet, just one landscape painting serves as a visual clue to the brief time when Eugene was his home.

Artists go to their sacred space to create. For some, it is a mental space to visualize artistic intentions. For others, the space is physical. I enjoy checking them out to discover what made them so seductive. Brett Whitley’s studio was an unassuming terrace house in a leafy suburb of Sydney — a place you could walk past and not even notice. Frida Kahlo filled La Casa Azul in Mexico City with the chaos of noisy, hairless dogs. On the other hand, it’s hard to imagine a more tranquil site than Claude Monet’s home in Giverny. Jackson Pollock – who I study – poured his way to fame in a windswept barn on the northern tip of Long Island. A contemporary of Pollock’s, where would Motherwell go in Eugene to find his special space?

Although Pollock captured the public’s imagination as the leader of the Abstract Expressionism movement, art scholars hold Motherwell in equal esteem. Their abstractions pushed the aesthetic envelope with such power that they shifted the focus of the art world from its traditional base of Paris to New York. Together, these artistic warriors scaled the rarefied peaks of Modern art using radical painting techniques – and their ascent was rapid. Within four years of leaving Eugene for New York, Motherwell had his first one-man show at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery, the Museum of Modern Art started to purchase his work, and he had become the leading spokesperson for avant-garde art in America.

In contrast to Pollock’s wild and drunken brawls, Motherwell’s reputation as the intellectual of Abstract Expressionism originated from his philosophy degree and his teaching at the UO. In reality, the latter came about as a compromise in his “cold war” with his father, who saw a teaching position as a more stable career move than Motherwell’s aspirations to become a painter. Family friend Lance Hart, an artist and teacher at the UO, served as peacemaker and suggested that Motherwell fill a temporary opening in the art department teaching courses in the history of modern art, aesthetics, and contemporary architecture.

In addition to his teaching, Motherwell worked on sets for a production of Pride and Prejudice at the Very Little Theatre in Eugene. He also exhibited drawings in local exhibitions, including at least one dedicated to faculty. The puzzle of why only one Oregon landscape painting survives might be explained by a challenge in his artistic development. He had recently enjoyed spending time in France but had reluctantly rushed home due to the impending war. Reminiscing about his time in Eugene, Motherwell recalled: “I spent a year learning … French intimate painting very well. I did some of it from postcards of France. I did some of it from nature in Oregon. But it was hard to do in Oregon because Oregon is very foresty and Scandinavian; and all that French thing is based on everything being parks and mannered and manicured and transformed by man.”

Motherwell left the university when his contract ended in the summer of 1940. An article in the Eugene Register-Guard from that June describes a student campaign to bring Motherwell back to the department: “Although his views were sometimes under fire … he can be credited with stimulating interest and discussion in his field. That is one of the prime functions of a teacher, it seems to us. … We launch this slogan: Motherwell back in the art school.”

With mention of “coming under fire,” perhaps his radical views on abstraction that would soon send aesthetic shock waves through the art world were already sending ripples through the UO classrooms? And perhaps the Oregon landscape painting serves as a rare record of Motherwell commencing his transition from his infatuation with French illustration towards his epic and very American abstractions. Art historian Harvard Arnason described Motherwell’s reaction to seeing the Oregon landscape painting years later: “Motherwell was able to recognize in it that naturalism was no longer anything but a pretext … he was already groping towards a kind of abstract automatism.”

The scene’s location remains mysterious, to the extent that it is unclear if it is real, imaginary, or a mixture of both. The recto inscription on the painting reads “For Valborg” and refers to Valborg Anderson, who taught English at the university. Katy Rogers, director of Motherwell’s catalogue raisonné, speculates: “Perhaps the Oregon Landscape is a rendering of where she lived in Oregon? Or someplace that the faculty would go to?” Much has changed in our local landscape over the 80 years since Motherwell and Anderson strolled around Eugene. Still, when I recall the thrill of seeing Renoir’s scenes with my own eyes, I hope that one rainy day in the future I’ll be walking my dogs and a casual look around me will trigger that thrill once again.

Richard Taylor is a professor of physics at the University of Oregon who studies nanoelectronics, neuroscience, retinal implants, solar cells, and the visual science of fractals.