A Shot in the Dark

Josh Frankel was the backup to the backup placekicker. But in a triple-overtime thriller against USC in 1999, his number was called.

By Charles Butler • Illustration by David Gill • July 12, 2023

11 min read[Editor’s note: This article was published prior to the UO’s August 4 decision to join the Big Ten.]

Josh Frankel figured the night would be . . . well, let’s just say uneventful, at least for him.

Considering Frankel’s spot on the Oregon football team—a walk-on, third-string placekicker—uneventful seems like the perfect adjective. You see, on this night, September 25, 1999, he had as much chance of influencing the outcome of the Ducks game against their Pac-10 rival, 16th-ranked USC, as someone working the concession stands. “I mean, as a backup you know you’re always one play away from playing, but as a backup to the backup—and as a kicker—you don’t think that’s going to happen,” Frankel says with a chuckle, his memory tracing back nearly a quarter century. “You’re there really to support your teammates, enjoy the experience, be part of the team, be part of something bigger than you—but not thinking you’re actually going to play a part in the game, especially when your starting kicker’s an All-American.”

At best, Frankel, a senior journalism major, held out hope that he might get on the Autzen Stadium field for a play or two. His dad, Allan, had flown in from Los Angeles for the game. “It was an early-season game,” Frankel says, “and there was a chance I might kick off once.”

For four quarters, all Frankel did was hang out on the Ducks sideline, keeping an eye on the topsy-turvy action on the field, like the 45,660 spectators. He watched as the lead changed hands three times and as penalties piled up (nearly three hundred yards between the two teams), causing the game to run four-plus hours. He witnessed three future NFL quarterbacks play critical roles, even though one of them—Joey Harrington—never tossed a pass or delivered a handoff. He looked up at the scoreboard as regulation time flipped into one overtime . . . and then another . . . and then . . .

And then, with the clock inching toward midnight, the night suddenly became very eventful for Josh Frankel.

Beating the giant

Before we get to that moment, let’s move the time machine forward to an approaching Saturday—November 11—when USC comes to Autzen to play the Ducks in what will likely be the last matchup between the two teams in Eugene for a very long time. S-C says “so long” to the Pac-12 Conference once the coming season wraps up. Along with UCLA, it’s moving to the Big Ten in 2024.

For sure, when it comes to Oregon rivals, USC is no Oregon State and certainly no Washington. But with eleven national championships, the Trojans are the team the Ducks (and others) have long measured their success against. And for the better part of eight decades, from their first meeting in 1915 through the 1993 game, USC ruled the rivalry (32–10–2). “Whenever we played [USC], particularly down in [the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum], it seemed like we had lost before we even got there. We were kind of intimidated,” says Nick Aliotti, 69, the Ducks defensive coordinator from 1999 to 2013. “Typically, if something went wrong early, it became like a big snowball rolling down the hill gathering steam.”

But that pattern flipped in 1994. The Ducks rolled to a 22–7 road victory—and later finished the season with a Rose Bowl bid, their first in thirty-seven years. “That ’94 game was a sort of a turning point,” Aliotti says. “We beat the giant.”

And since then, the record stands: Ducks 12 wins, Giants 7.

“It’s the dream of a small-town guy”

Now, let’s get back to the ’99 game, perhaps the best game ever between the Ducks and Trojans at Autzen. Even those with foggy memories about all the particulars of that night—like Mike Bellotti—realize the impact that game had on a third-string kicker. Bellotti, who was in his fifth season as Ducks coach, needed YouTube to refresh his recall of the game, though some details remain lasting: that his Saturday started at 7 a.m., that his postgame press conference didn’t end until 12:45 a.m. Sunday—and that his third-string kicker played a momentous role. “His life changed that night,” Bellotti, 72, the Ducks’ all-time winningest coach, says of Frankel.

Overcast skies loomed when the game kicked off at 7:25 p.m. Autzen was packed. USC, 2–0, came out in white tops and gold-colored pants, both trimmed in Cardinal red; the Ducks, 2–1 (including an opening-season loss to Michigan State), played in green uniforms and with helmets featuring a logo—the now familiar “O”—that had only recently been adopted. USC was led by a sophomore quarterback, Carson Palmer, who would win the Heisman Trophy three years later. The Ducks had A. J. Feeley calling plays.

Mike Jorgensen, a former Oregon quarterback who was then in his tenth season as the color analyst on Ducks radio broadcasts, remembers feeling a well of pride with Feeley in charge. Both he and Feeley came from Ontario, Oregon, a town of barely eleven thousand people near the Idaho border. “Not a whole lot of small-town guys get the chance to play for Oregon,” says Jorgensen, 60, the Ducks starting quarterback in 1983. “As a small-town kid growing up on the east side of the state and in a completely different time zone, to see one of my homeboys doing the job on USC in Autzen Stadium . . . it’s the dream of a small-town guy. And at the time USC was still the biggest name. People may have hated Oregon State or Washington, but USC was the team to beat.”

The teams were even at halftime, 10–10, but USC went into the third quarter minus Palmer. He had suffered a broken collarbone right before the break on a hit by Oregon safety Michael Fletcher. By the third quarter, the Ducks held what seemed like a comfortable 20–10 lead, built on a Feeley touchdown pass and Nathan Villegas’s second field goal.

Villegas had been a spot-on kicker for the Ducks, once connecting on fourteen consecutive field goals to set a school record. The previous season he was a finalist for the Lou Groza Award, which recognizes the nation’s top collegiate placekicker. And, like many of his teammates, he was a SoCal recruit who enjoyed facing USC. “We were playing against guys we played against in high school,” Villegas, now a sales trainer near Houston, says, “so it was more of a hometown rivalry.”

And the rivalry’s intensity cranked up during a chaotic fourth quarter. Palmer’s replacement, Mike Van Raaphorst, led the Trojans on two 70-plus-yard touchdown drives, the second one putting USC up, 23–20, with just over three minutes to go. But a botched extra point gave the Ducks—and Villegas—life. With less than three minutes to play, Feeley led the Ducks from deep in their territory into the Trojans’. Villegas, on the sideline taking practice swings with his right leg, waited for a signal from Bellotti. “I wanted to be on the field. I wasn’t scared of it, I didn’t shy away from it,” Villegas remembers. Once the Ducks crossed the 50-yard line, he told Bellotti, “I’m ready when you are.”

“Being a Southern California boy,” Villegas adds, “to have that opportunity to give our team a chance to beat them, I was looking forward to it.”

His time came with thirty seconds left in regulation. Villegas set up on the right hash mark for a 26-yarder. His holder was Joey Harrington, who by season’s end would be the Ducks starting quarterback. As he had done twenty-six out of his previous thirty attempts, Villegas sent his kick easily through the uprights, tying the score at 23, and setting off a delirious celebration among the remaining fans in Autzen.

But on the field the celebration was more awkward—and costly. Harrington and Villegas both leaped after the kick, and then Harrington tried to hug his kicker from behind. But while trying to turn, Villegas got his right foot stuck in the turf. His knee twisted and he crumpled to the ground. Villegas was carried off the field by two teammates, his night over. He had a torn ACL that would jeopardize the Ducks’ chances of beating beat USC—and severely limit his future football career.

“If they don’t have him going into the extra period,” Steve Physioc, Fox Sports Net’s play-by-play announcer, told viewers, “what a huge loss that would be.”

But the backup to the backup placekicker would not let the night go dark for Oregon.

A snap, a kick, a shot at history

After a scoreless first overtime, the Ducks took the lead in the second on a short Feeley touchdown pass. Bellotti then faced a crucial call: go with second-stringer Dan Katz to kick the extra point or try Josh Frankel. Katz, used mostly on kickoffs, had badly missed a possible game-winning field goal attempt in the first overtime. That miss made Bellotti’s choice—Frankel—a bit easier, although it caught Frankel off guard. He still had Villegas on his mind. “He’s a close friend,” Frankel says, “and I’m thinking about him more than thinking I’m gonna get into the game.”

Frankel was not a stranger to pressure. As a freshman in 1996, he kicked two extra points against Washington. The following year, he became a mid-season starter, helping the Ducks upset no. 6 Washington, 31–28, with a field goal and four extra points. But when the All-American Villegas arrived for the 1998 season, Frankel moved back in the depth chart—until moving back front and center on this late September night. His extra point gave Oregon a 30–23 lead.

“[Frankel] relished the opportunity to compete in practice,” Bellotti says. “You see that [competitiveness] in the guy’s eyes.”

USC matched the score on their next drive, forcing a third overtime—and what turned out to be a showdown between placekickers. USC’s David Newbury had the chance to give the Trojans the lead, but a 37-yard attempt fell short, his third miss of the game. Ducks ball. Two rushes by Derien Latimer set up a first and ten from the USC 11-yard line. Frankel figured Bellotti would use a couple plays, inch the ball closer, maybe secure the win with a touchdown. Instead, on first down, Frankel got the call.

“[Frankel] relished the opportunity to compete in practice. You see that in the guy’s eyes.”

—Mike Bellotti

“It was a Rudy-type moment where the third stringer comes on with a chance to win the game,” says the kicker who grew up in Pacific Palisades, California, fifteen miles from Hollywood, referencing the 1993 sports-drama film. “Nobody would have drawn up that script. Fortunately, my mind was very clear. I was just excited to be there and didn’t really have time to digest the significance of the play. It was probably a lot more stressful for my mom watching on TV.”

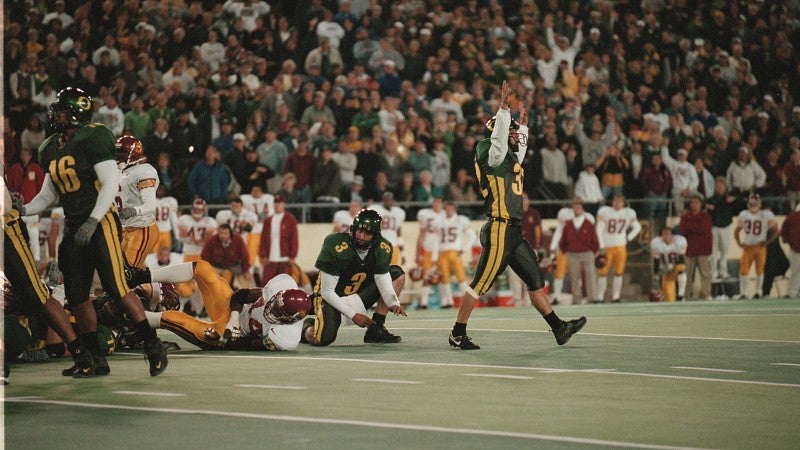

The snap came to Harrington. Frankel took three strides toward the planted ball, swung his right leg like a seven iron and secured a 33–30 win for the Ducks. And, as Jorgensen says, “etch his name in history.”

Teammates mobbed Frankel, lifting no. 32 off the ground and carrying him across the field. He was swarmed by Oregon fans, who had waited four hours and twenty minutes for the game’s outcome. Eventually, he found his father. “It’s a moment I will always cherish, especially that he is no longer here,” Frankel says of the hug he shared with his dad, who died in 2021. “To have that moment together was very, very special.”

In the Ducks training room, Nathan Villegas was dealing with different emotions. Until that night, he had NFL scouts in pursuit. But while he eventually returned to play in a few of the Ducks’ remaining games that season, he went undrafted, teams scared off by the torn ACL. He has spent his post-Oregon years working in sales, satisfied with his personal and professional life, but aware of what a freak injury cost him. “I love Josh Frankel. He’s a great dude and it was awesome to see him make that kick,” says Villegas, 46, who, with his wife, Crystal, is raising five children. “Of course, it sucked for me because it was the only opportunity I [would have] in college to get a game-winning field goal.”

Frankel, 45, finished his football career the following season and has been in the financial service business for the past fifteen years. In 2021, he received the Leo Harris Award, which honors a UO alumni letterman. His days are now busy with work and, with his wife, Amy, raising three kids in the Portland area. “There was a point in time where [the kick] was the greatest moment in my life, but now with kids and other things . . . ” Frankel says, chuckling. But every now and then, someone will recognize him and ask, “Are you that Josh Frankel?” And when he walks by his eleven-year-old son’s bedroom, he’ll see a photo of “The Kick” hanging from a wall. And buried somewhere in his garage is the game ball his teammates gave the walk-on after his 27-yarder. And some nights he’ll go to YouTube and watch a grainy video from twenty-four years ago, and then he’ll share what he sees with kids who were not in Autzen Stadium the night no. 32, the backup to the backup, beat the giant.

“I’ve used that as a lesson now that I’m coaching a lot of my kids’ sports,” Frankel says. “Just always be ready. You truly don’t know when your number will be called.”

Charles Butler is an instructor in the School of Journalism and Communication.

The Ducks open the 2023 season against Portland State Saturday, Sept. 2, at noon PT in Autzen Stadium. They host USC November 11.