The Solitary Genius

Who Sparked a Global Revolution

Legendary coach Bill Bowerman spurred TrackTown USA and a stream of innovations in footwear and performance

By John Brant • Illustration by David Gill • April 12, 2023

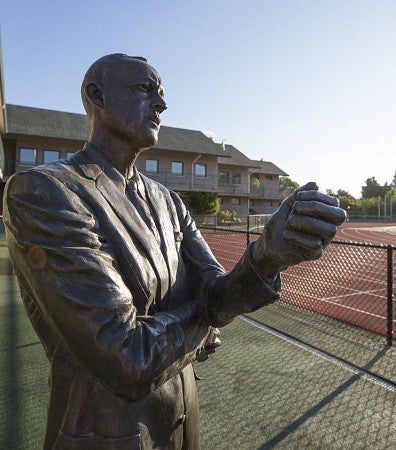

12 min readHayward Field at the University of Oregon served as Bill Bowerman’s classroom and lab as well as his arena, and the stadium that grew into a globally recognized shrine for track and field during his twenty-four-year tenure at the school remains the single best place to learn about the man; a display in the Hayward Field visitors center traces Bowerman’s landmark career as coach, educator, inventor, and entrepreneur. But such was his impact on the university, the city of Eugene, and the world beyond that multiple sites around town and campus bear the Bowerman stamp.

The corner of East Fifteenth Avenue and Agate Street, for instance, just a few steps away from Hayward Field’s ten-story tower. Here, on a Saturday morning in 1965, a twenty-seven-year-old psychologist at the Oregon Research Institute encountered Bowerman. “I had come to Eugene from the University of Michigan the year before, and it was like I’d entered a different country,” recalls Paul Slovic, today a prominent professor of psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences. “In the rest of America virtually no adult exercised, much less jogged or ran. My own father was quite overweight. Every Fourth of July he entered a ‘fat man’s race’ in our town that everyone thought was hilarious.”

To keep in shape, Slovic had tried running the streets of Ann Arbor but passing motorists either swerved around him in fright or stopped to offer him a ride to the hospital. “Then I came to Eugene to find people of all ages running around town, as if it was the most natural thing in the world,” Slovic says. “Was this America?” It was; a far corner of the nation prophetically reimagined by Bowerman.

The new documentary Heart of Tracktown, produced by Dustin Whitaker and University Communications, celebrates the running community that grew from the legacy of Bill Bowerman and other track legends

In 1962 Bowerman had taken his UO track team, starring the sub-4-minute miler Dyrol Burleson, to New Zealand for a series of meets with a team coached by the legendary Arthur Lydiard and led by Olympic champion middle-distance runner Peter Snell.

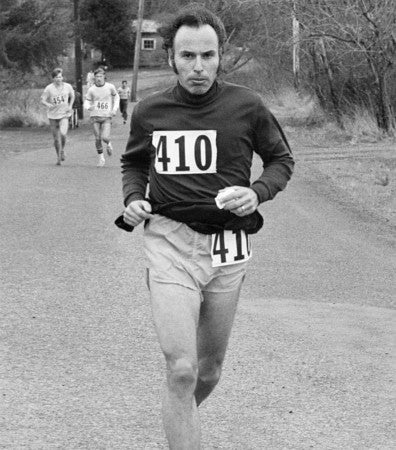

The events that transpired demonstrated a recurrent, dominant theme in Bowerman’s work: applying the dictates of world-class competitors to the needs of everyday citizens. In New Zealand, Bowerman was stunned to see crowds of ordinary people jogging, using the guidelines that Lydiard had developed for his competitive athletes and then promoted for the community’s general health, covering mile after mile at what Lydiard prescribed as “a conversational pace.” Like Lydiard, Bowerman grasped the simple but revolutionary concept that the principles of aerobic training worked the same for everybody, be they an Olympic medal winner or a middle-aged individual recovering from a heart attack. Bowerman, too, started jogging, and a few weeks later came home to Eugene energized and ten pounds lighter.

Another coach might have shared his discovery with family and friends, then gone about his business. But Bowerman thought differently. He put out word to town and gown: come to Hayward Field to try this new thing called jogging. Twenty people showed up the first time, with the numbers swelling each weekend thereafter.

Soon, people were running all around campus and environs, and Bowerman and cardiologist Waldo Harris were conducting a study of Eugene’s citizen runners that would form the basis for their 1966 book Jogging. The book became an international bestseller and ignited a boom in physical fitness in general, and running in particular, that has spread around the globe to incalculable benefit. At home in Eugene, the Bowerman-inspired citizen runners formed a pillar in the interlocking architecture of TrackTown, USA.

Slovic personified the elements comprising Eugene’s new identity. He joined the Oregon Track Club, ran marathons and other road and trail races, and became a diehard member of the Noon Group, a disparate, informal crew that gathered each midday for an hour’s run. The runners often warmed up with a lap or two at Hayward Field, where Bowerman welcomed them.

“It was a visionary achievement to start the age of jogging. [It] has improved the lives of millions around the world.”

—Paul Slovic

Remembering that Saturday morning in 1965, Slovic recalls Bowerman, clipboard in hand, a commanding presence, directing schoolteachers, mill workers, store clerks, and students to jog their various distances while exploring Hendricks Park and the neighborhoods around campus. “It was a visionary achievement to start the age of running and jogging,” Slovic says. “One that has improved the lives of millions around the world.”

In a basement lab, reimagining the running shoe

Continuing the Bowerman tour, step away from Hayward Field and the university campus and venture into downtown Eugene.

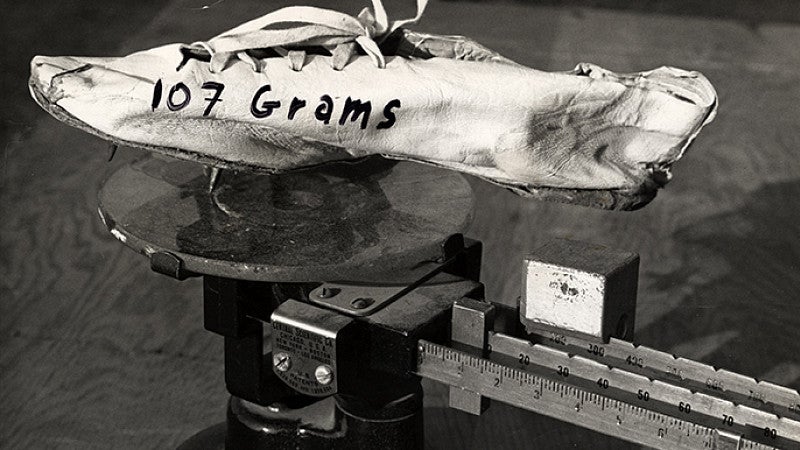

Throughout his earlier years at the UO, frustrated by the inferior quality of American-made track shoes and the high cost of German-made ones, Bowerman cobbled shoes for his athletes, striving to combine lightness and cushioning with the goals of performance and injury prevention. With the advent of the running boom that he largely inspired, Bowerman began designing good shoes for the everyday athlete. That led to partnering with Phil Knight, Bowerman’s former Ducks runner, to start Blue Ribbon Sports in 1964. BSR grew into Nike, and the rest, of course, is history.

During the 1970s and ’80s after retiring as the UO track coach, Bowerman operated his own shoe lab under Nike auspices. Here, at a small space in the basement of an office building on East Broadway, he employed a young Ellen Schmidt-Devlin, now executive director and cofounder of the UO sports product management program in the Lundquist College of Business.

In 1976, Schmidt-Devlin, a fifth-generation Oregonian whose family owned a hardware store in the mid-Willamette Valley town of Albany, was running in her first cross-country meet as a Duck. Perhaps Bowerman, whose grandparents founded the town of Fossil in Eastern Oregon, detected a flinty pioneer streak in the young woman. He approached Schmidt-Devlin after her event.

“Hi, I’m Bill Bowerman. Would you get the girls on your team to test Nike shoes?”

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Bowerman,” Schmidt-Devlin responded. “But we are not girls. We are women.”

In 1981, after Schmidt-Devlin graduated from the UO, Bowerman hired her as a full-time Nike employee, assisting him in his basement shoe lab. She continued to test-run his prototype shoes, learning that if age had softened her boss’s old-school, tough-love edge, it hadn’t disappeared entirely.

“Bill would try all kinds of wild ideas,” Schmidt-Devlin says. “Once he made these shoes with these enormous metal shanks in the sole and heel. I wore them for a training run and the metal sliced into my calves and cut them up pretty thoroughly.” She limped back to the lab, shoes in hand. “I told Bill, ‘What a terrible idea! Look what they did to me!’ Bill started laughing. ‘I thought you’d be smart enough to stop running if your shoes hurt.’”

“Bill was that rare bird—a basically solitary genius who also felt, and enacted, a deep responsibility to his community.”

—Ellen Schmidt-Devlin

The gruff humor was offset by his warmth and deep concern for others. “Bill didn’t make shoes just for runners and athletes,” Schmidt-Devlin says. “Parents with kids with special needs would come to him, and doctors hoping to get their patients to exercise.” Yet again, Bowerman applied ideas derived from the elite to everyday people.

“Bill was that rare bird,” says Schmidt-Devlin. “A basically solitary genius who also felt, and enacted, a deep responsibility to his community.”

Peak performance for elite athletes and weekend warriors

For the next stop on the tour, return to Hayward Field, dodging the skateboarders clacking over the brickwork in front of the stadium. Go several yards toward campus and notice a small glass door at the corner of the stadium, entryway to the Bowerman Sports Science Center.

Researchers there study performance physiology using lactate threshold, VO2 max, heart rate, and body composition; and running biomechanics using force platforms, accelerometers, and high-speed cameras—all toward determining how to scientifically make the most out of every training day, and how to specifically tailor that training for each individual, says Mike Hahn, director and a professor of human physiology in the College of Arts and Sciences.

The BSSC’s core mission, however, consists of translating that research to the benefit of the general population. “Performance-based research turns traditional medical research on its head,” Hahn says. “Instead of starting from disease, we start from health—by studying what works for the supremely healthy rather than what’s gone wrong for the ill.”

Employing twenty-first-century technology, in short, the BSSC continues the work that Bill Bowerman started by using a stopwatch, a cobbler’s blade, and his wife’s waffle iron—the humble kitchen tool inspiring Bowerman’s signature invention, the Nike waffle-soled training shoe.

The center’s unprepossessing glass door opens to a gleaming high-tech wonderland. Human physiology professor John Halliwill presents a room with force-measuring plates embedded in the floor of a treadmill, with eight video cameras capturing a runner in 3-D motion, so researchers can calculate the internal mechanics of the muscles, tendons, and joints. Nearby is a chamber where every conceivable environment for human movement can be simulated, from Saharan heat to Arctic cold, jungle humidity to desert aridity, and where a machine can effect tempestuous headwinds.

Impressive, but what would the lone wizard Bowerman think of all this gear? Could masses of scientific data overshadow the artist’s intuitive insight that animated the thousands of pages of individualized training schedules that Bowerman wrote for his athletes?

“Bowerman was a wonder in so many ways,” Phil Knight writes in his foreword to Bowerman and the Men of Oregon. “He had no assistant coach. No secretary. Written out in longhand for each of the 35 athletes, he tailored individual workout sheets every week of the school year. In my four years, that amounted to 4200 individualized workout sheets; 120 of them were mine.”

Kenny Moore, author of Bowerman and the Men of Oregon, put the matter succinctly. “His training system rested on the deceptively simple truth that all runners are different.”

Halliwill says that Bowerman’s creative spirit and focus on the individual live on at BSSC. “The art in what we do lies in communicating the data to the individual coach and individual athlete,” he says, then pauses for a beat. “Bowerman was a coach, but he was also a full-time faculty member. Bill talked to professors in all the school’s departments, to administrators in all the offices, and he recognized the obligation the school had to the community. Bill was all about crossing boundaries—between science and art, between Olympic athletes and the everyday runner. That’s our goal here at the center—to cross boundaries. To study exceptional human performance in order to boost the health of everybody.”

“Me time” and encouraging words from the track coach

Bill Bowerman’s influence in Eugene and the UO campus is so pervasive that it’s become part of the ambient atmosphere. Many younger residents and students may not realize that the shoes they run in, be they Nikes or another brand, owe their basic design to Bowerman, or that the routes they run on, such as Pre’s Trail, were originally plotted by Bowerman and his athletes. “I’m aware of his story,” says third-year undergraduate student Kayla Krueger. “But most of my friends know more about Phil Knight than Bowerman.” That fact would no doubt please Bowerman, who never sought the limelight, and who always placed his students and athletes first.

Majoring in journalism with minors in French and political science and working three part-time jobs, Krueger still makes time to run every day. She started to run in 2020 during her senior year at Lakeridge High School in Lake Oswego. “I’m not a naturally talented distance runner,” she says. “It’s very humbling to try something new when you’re not good at it.”

Nonetheless, Krueger grew devoted to the sport. “The way it makes me feel, the emotional release. I think I would’ve kept running no matter where I went to college, but here in Eugene, where there’s so many great places to run, and so much encouragement, I almost feel obligated to run. I’d be doing a disservice to myself if I didn’t take advantage of what the town has to offer.”

In 2022, Krueger decided to run the Eugene marathon, finishing in 5:02. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but maybe the most rewarding,” she says. “Now here I am training for the 2023 race. Two marathons, just one year apart!”

“In Eugene, where there’s so many great places to run, and so much encouragement, I almost feel obligated to run.”

—Kayla Krueger

Eugene offers plentiful opportunities for training in a group or club, but Krueger mostly runs alone. “My friends think I’m crazy when I go out solo for fifteen miles. But I’m around people all the time. Running is my ‘me time,’ a chance to reflect and recharge.”

Even while running solo, however, she stays connected to TrackTown, joined to a community of kindred spirits that started more than sixty years ago, when Bill Bowerman stood with his clipboard at East Fifteenth Avenue and Agate Street, encouraging the joggers, or when he welcomed the citizens starting their run at Hayward Field.

“One day recently I was out on Amazon Trail where the U of O men’s track team was doing a workout,” Krueger says. “Jerry Schumacher, the head coach, sees me chugging along. He smiles and says, ‘Great job, looking good!’ The head coach of a D-1 track team paying attention to me—I’m not sure that would happen at another school, or anywhere but Eugene.”

A personal response to every letter

You might conclude your Bowerman tour back on campus, in the Paulson Reading Room of the Knight Library, where archivist Lauren Goss presides over the papers that document the life of the legendary coach, who died in 1999. Here you will find boxes of correspondence and other material covering all aspects of his career, encompassing the birth and growth of Nike, plans for the 1972 Olympic trials at Hayward Field, letters to and from Adi Dassler, founder of Adidas, and Kihachiro Onitsuka, founder of Asics, as well as correspondence with hundreds of people who came to him with questions about jogging with a heart condition or what classes to take. Included, too, are hundreds of hand-written pages of individualized training schedules.

Sunday--long run, 10 miles.... Monday--light easy jogging, 10 x 300 meters on grass...Tuesday-- intervals, 10 x 200 meters, 75 seconds per rep...

“It’s fascinating to meet Bowerman through stacks of yellowed sheets of paper,” Goss says. “You see his philosophy embodied in actual plans. His emphasis on recovery days for his runners, the hard-easy system that we take for granted now but was revolutionary when Bill used it. And he jiggered and tailored that system for each individual he trained. He wrote out plans for every athlete, all events. You get a sense of his curiosity and hunger to experiment. Those long, thoughtful exchanges with Arthur Lydiard. And his correspondence with average people. ‘What kind of shoes should I buy?’ Bill personally answered every letter.”

Bill Bowerman would qualify as a towering figure if he stood on just one pillar of his career. For jogging alone he’d be a giant, or for shoemaking and Nike, or for the individualized training that produced eleven sub-4-minute milers, twenty-five individual NCAA champions, thirty-three Olympians, sixty-four All-Americans, and twenty-five US record holders.

At the same time, however, none of the three pillars of his career would have stood without the support of the other two. Bill Bowerman—coach, educator, inventor, and entrepreneur—was both a multi-dimensional genius, and all of a piece. He was also deeply—almost mystically—rooted in the state of Oregon, the UO, and the Eugene community. Reading through his letters in the Knight Library, or standing by his statue at Hayward Field, you’re struck by the thought that Bill Bowerman’s genius might have shone in many different professions, but could only fully flower here in TrackTown USA.

John Brant is a longtime writer-at-large for Runner’s World and he contributes to publications ranging from Outside to the New York Times Magazine.