This year Juneteenth, Freedom Day—Friday, June 19—is a poignant reminder of freedoms still not won, and of hope among those of us who continue to fight for change.

Juneteenth commemorates the day in 1865 that Union soldiers in Texas announced the Confederacy had surrendered two months earlier and enslaved people were free—two-and-a-half years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

To mark the day, Oregon Quarterly talked to faculty members, alumni, and administrators—thought leaders in their fields—for reactions to George Floyd’s death and uprisings across the world as the Black Lives Matter movement gains historic momentum.

In light of the Black Lives Matter movement, what questions are you asking yourself?

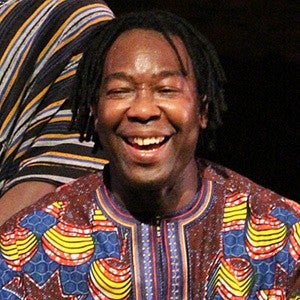

Iddrisu: The Pledge of Allegiance states, “With liberty and justice for all.” Children are taught to recite these words from a young age, yet liberty and justice are not applied to everyone. I ask myself, how can that be? While I am hopeful for change, I find myself asking if this is one of those same scenarios where people get upset, and then it goes nowhere? Or is this time different? With the outrage across the globe, will it make this different than what we’ve experienced all these years?

Warren: What will the world look like in five to 10 years? How will this moment affect my nine-year-old daughter’s life? Will this movement have the momentum needed to spur us to real change? Though the current events and climate seem to have merged to cause this eruption in civil unrest, I wonder if we collectively have the stamina needed to do the real work of equity.

Dawson: What am I doing to reverse racist policies and practices? I am looking for ways to get uncomfortable and to learn more about the lived experiences of my Black students and colleagues. I am thinking about the power and privilege my whiteness has afforded, and how I can use my influence to help UO and the Eugene community to learn, grow, and change until the current systems of oppression are overturned.

Lowndes: I’m wondering how far this can go. As a result of hundreds of thousands of people demonstrating day after day and night after night, the public conversation around the persistent problem of police violence has now shifted from reform to defunding or outright abolition of police departments. That is a dramatic change, and it happened very quickly. It remains to be seen whether the result will be lip service, or whether what presently falls on police to do will shift to social service agencies, mental health services, anti-poverty and housing programs, et cetera. In other words, will municipalities and other local governments continue to approach seemingly intractable social and economic problems as law enforcement problems, or will they seek resolutions elsewhere?

From your field of expertise, what questions should we be asking about Black Lives Matter and race activism?

Warren: The work of equity includes the shift of power, and the journey toward the balance of power is a long one. Those in the dominant culture can take the first step by asking themselves, “How do we properly value humanity? What do we need to feel respected, valued? What do we need to live and care for our families?” And then realize black and brown people need, want, and deserve the same things. Then ask, “How can I use my privilege and power to build from that place?”

Dawson: As an advocate for inclusive teaching practices, I think we should be questioning every hurdle in a Black student’s academic path, looking for places that our systems and actions are racist. Faculty members must confront beliefs that lead to “gatekeeping,” and critique their content, illustrations, authors, narratives, grading practices, and “teacher talk,” looking for their own biases and racist behaviors.

Yu: As academics, we do not exist in a vacuum and it is important to recognize the current events: Black members of our communities are being harassed and dying with little to no consequence, as well as being disproportionately affected by the current pandemic. We need to acknowledge that this takes a toll on the well-being of Black academics and that Black Lives Matter. The June 10 Strike for Black Lives arose from the questions: “How are we, as academics, complicit in anti-Black racism and how can we change this?” Although I am heartened to finally see these issues being discussed openly, we also have to remember that we cannot erase hundreds of years of racism in the course of a day. Real change will take much concentrated, and often times difficult, sustained action. This requires accepting that there is a baseline of racism in the way our academic institutions operate.

Iddrisu: There is a proverb from my culture: “Until lions can have their own historians, the tale of the hunt shall always glorify the hunter.” So much of what has been written about Black people and Black culture is negative—wars, famine, slavery. Positive contributions are ignored or minimized. Yet, white culture borrows heavily from others. How do we change this narrative? How do we ensure that our young Black people can be the voice that reflects true Black culture? How do we ensure that there are Black people in the universities and involved in curriculum development when there are decisions about how to present Black history and culture? What will it take to get representative people in positions of power when deciding what is valuable?

Through the protests against police and the calls for racial justice, what thought or feeling is running through your mind?

Iddrisu: It is so difficult to be a Black person in this culture. You are constantly reminded that you are not important—from the grocery store to an oil change to the workplace. In daily life, you get a racist gaze or someone asking you, “Why are you here? Why don’t you go back where you came from?” Like most Black people, I try to look above what we see every day and not let those daily reminders pull me down. But it is still not OK. During these times when a spotlight is shining on the injustices those with my skin face every day, I think about not wanting someone else’s ignorance to make me less than I think I am. But I also wonder what it will take to change the systems that allow that ignorance to thrive.

Warren: I feel sadness and anger about the abuse of authority and the dishonorable code that encourages silence and deafness regarding the reprehensible acts against Black people. I also feel hopeful the unrest may be loud enough to cause leaders to listen and push them towards meaningful and sustainable change.

Dawson: Equal parts outrage and optimism. This is the largest-scale awakening to racism I have witnessed in my lifetime, and it gives me hope that more white people will have the courage to engage in difficult conversations and to listen with love, authenticity, and empathy to what our Black friends and colleagues have been trying to tell us all along.

Lowndes: Every major social reform in US history has required militant agitation and disruption in the streets, from the American Revolution to the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, the labor movement, the Black freedom struggle, the fight for LGBTQ rights, and the anti-nuclear movement, among others. The constitutional framework of the US political system creates enormous barriers to social change. Outside pressure is often the only avenue. A majority of Americans support the protests. Surprisingly, 54 percent of Americans even supported the burning down of the 3rd precinct in Minneapolis. I’ll be honest here. I am inspired by the protesters—their courage in the face of brutal tactics, their stamina, their refusal to be mollified by empty promises. These are often democracy’s best moments, ones that should give us hope at a time when we don’t have a lot of it.

Cheney: The phrase “Black Lives Matter” only has meaning when one recognizes that origins of “Blackness” were created in diametric opposition to white humanity. Since the period of enslavement, the conspiracy of white power was built upon anti-Black violence or the threat of anti-Black violence—even in places that outlawed slavery. Oregon’s original “lash law” was passed alongside its first exclusion law in 1844. Forty-eight years later, activist-journalist Ida B. Wells exposed racist mythologies justifying the lynching of Blacks in the American South. The act of racial terrorism that resulted in the 1955 death of Emmett Till inspired modern Civil Rights movement activists such as Rosa Parks and Stokely Carmichael. Police harassment and brutality in California was the catalyst for the political intervention of the Black Panther Party in 1966 and the cultural intervention of NWA’s “Fuck Tha Police” in 1988. Anti-Black violence is the nation’s historical legacy. The accessibility and pervasiveness of digital technologies provide painful and repetitive reminders of our physical vulnerabilities vis-a-vis the state and white publics. But this is not new news. Same white shit, different Black bodies. May their deaths not be in vain. Rest in power.

Anna Glavash Miller, MS '18 (journalism), is a communications generalist in the Clark Honors College. Emily Halnon is a staff writer for University Communications.