From Arafat to the Dalai Lama, Alum Shielded Leaders

Special agent Cam Burks ’96 put himself in harm’s way for the US and global dignitaries

By Rosemary Camozzi • Illustration by David Gill • July 3, 2024

6 min read

If you run into University of Oregon alumnus Cam Burks at a backyard barbecue, you’ll probably end up talking about fly fishing on the McKenzie River or powder skiing at Tahoe. The 1996 sociology graduate might mention his daughter’s interest in physics or a recent family trip to Patagonia.

You’d never guess that this mellow, outdoorsy dad has led a life of danger and intrigue as a special agent for the US government, protecting international dignitaries and overseeing security at embassies around the world.

When Burks arrived at the UO in 1992, he had no idea what to study, but an introductory sociology class grabbed his attention. “It appealed to my curiosity about what makes people tick,” he says. Sociology professor Ken Liberman, who became his advisor, sealed the deal. “All of us students really took to him,” Burks says. “He was this incredibly smart person, but he was also a surfer and completely laid-back.

“Those were formative years for me,” he adds. “I found a group of friends and professors who were very smart and professional, but they were also mellow and fun. I learned that I could succeed by being who I was.”

“I wore a little wire in the ear, the black suit and sunglasses, all that stuff.”

—Cam Burks

In his junior year, Burks was offered a full-term internship in Washington, DC. He was assigned to the Bureau of Diplomatic Security, the law enforcement and security arm of the State Department, and worked in an office that protected classified information. He was later transferred to the San Francisco field office, where he assisted agents and joined protective details for foreign ministers. Along the way, he began to learn the workings of the intelligence community. “I realized that this amazing organization has a tangible impact on our national security,” Burks says. “The agents were just really good people, and I saw the difference they were making. I immediately knew I wanted to be a special agent.”

Burks went on to earn a master’s degree in criminal justice at California State University, Sacramento. In 1997 he joined the Diplomatic Security Service, where he was trained in firearms, defensive tactics, and driving in motorcades. This wasn’t your normal driver’s ed: Burks learned how to ram vehicles, fire weapons from a moving car, and conduct high-speed “J-turns”—driving backward and then swinging the car around to face forward.

While at the training academy, Burks occasionally worried about the risks of his career choice. To ease fears, he asked the most questions of anyone in his class. “This line of work is very dangerous, and I took that very seriously,” he says. “I didn’t take anything for granted. I knew what I was getting into.”

Once he became an agent, Burks worked on criminal investigations, made arrests, and testified before grand juries and at trials. Most of his work revolved around pursuing foreign criminals who obtained fraudulent US passports under a false identity, typically in furtherance of another crime such as drug smuggling, human trafficking, or terrorism.

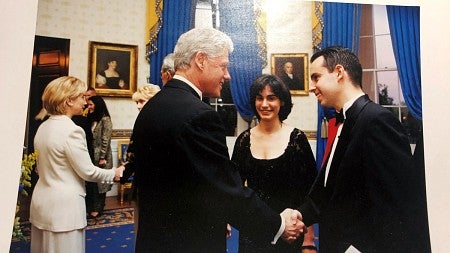

In 2000, Burks joined the protective detail for Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. “I wore a little wire in the ear, the black suit and sunglasses, all that stuff,” he says with a laugh. Albright learned the names of the agents who protected her and took a genuine interest in their lives. “She was a role model for so many,” Burks says, “trailblazing as the first female secretary and standing up to world leaders around the globe. She treated her special agents with dignity and respect—she always supported us and had a genuine and kind human side.”

Burks also managed security for Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat at President Clinton’s Camp David Summit in 2000. At an event in Washington DC, broadcast live, a CNN anchor and Arafat began to argue. “Arafat stood up and started screaming at him,” Burks says. “He was enraged, with a deep red face, and we thought there would be a physical altercation.” Although known for his temper, Burks says, Arafat was always respectful to the agents protecting him.

Burks went overseas after the September 11 attacks to head up the Regional Security Office at the American embassy in Dhaka, Bangladesh. At one point, the embassy received a threat that a training camp of US Peace Corps volunteers near Dhaka would be attacked. Working with the Bangladeshi government, Burks sent in a military convoy and evacuated the group—all two hundred of them—in the middle of the night. “I was very concerned for their safety,” he says. “As the caravan approached Dhaka, I felt great relief. I personally knew most of them, and we often had volunteers over to our house for a home-cooked meal.”

In 2003, the US invasion of Iraq triggered massive protests in Dhaka. Almost every Friday for months, Burks says, more than one hundred thousand angry people gathered across the street from the US embassy, where a line of police prevented them from entering the compound. “There was a line of police, then me, six Marines, and one political attaché inside the embassy, ready to destroy classified information and shut everything down,” Burks says. “It was a harrowing time.”

After learning to speak fluent Romanian, Burks managed security for the American embassy in Moldova, a former Soviet state. He also led the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency’s criminal investigation against New Jersey millionaire Anthony Mark Bianchi, who was convicted of child sex abuse in Moldova and Romania and sentenced to twenty-five years in federal prison.

Burks’s wife and two young daughters always accompanied him overseas. The family’s social scene included barbecues, a softball league, and evening tennis tournaments. “It was wonderful to have them there,” he says. “They were truly part of the State Department family, and we became lifelong friends with other diplomatic and expat families.”

There were tense times, too, in various countries where the family resided. After a threat was made against Burks, an army detail was activated to protect their house for months. At another point, his family locked themselves in their home’s saferoom while throngs of anti-US protesters marched down their street. “But all in all, it was a great experience for my wife and kids,” he says. “We traveled the world and learned to appreciate so many different cultures.”

After returning to Washington, DC, in 2008, Burks rejoined the security service as chief of staff to the director and an advisor on counterterrorism and counterintelligence. In 2010, he left to join Chevron as deputy chief security officer, managing global security. The move enabled Burks and his family to return to the Bay Area—Burks hails from Burlingame, California—and his training came in handy, as the company drew frequent protests against oil and gas extraction. “We had to protect the CEO at his home all the time,” Burks says.

Settling in Lafayette, California, Burks worked at Chevron for about eight years. He also served his city: after being appointed chair of Lafayette’s crime prevention commission, he was elected twice to the city council and served as mayor from 2019 to 2020.

Today Burks is vice president for global safety and security at Roku, the digital media player company. He is also a senior fellow at George Mason University’s National Security Institute and an affiliate of Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation. The positions enable Burks to keep up with “the geopolitical risk side of the business,” he says.

Certain periods of his life as a special agent still hold a special resonance for him. When the 14th Dalai Lama was in the US in 2001–2002, Burks managed the spiritual leader’s security detail. He fondly recalls a poignant moment at the end of the visit, when he was escorting the Dalai Lama to his plane at Dulles International Airport near Washington, DC.

“He got on the plane and I turned around to walk back up the ramp,” Burks says. “Then I heard footsteps behind me. He was running back to give me a hug, and he gave me five or six pats on the back.

“We maintained a very professional relationship,” he says, “but his kindness and generosity were not lost on me.”

Rosemary Howe Camozzi, BA ’96 (magazine), is a freelance writer and editor in Eugene.

Images courtesy Cam Burks, BS ’96 (sociology).