Looking Back on Fifty Years, and Ahead to a Feminist Future

With courage, determination, and a bit of good fortune, a group of University of Oregon scholars created a center to spotlight and confront gender inequality

By Alice Tallmadge • Images courtesy Center for the Study of Women in Society • January 17, 2024

8 min read

The Center for the Study of Women in Society at the University of Oregon has for decades been an academic powerhouse, generating groundbreaking, gender-focused research, incubating innovative projects, and launching cutting-edge ideas into the university and beyond. It has been a hub of intersectional and interdisciplinary collaboration, feminist activism, and scholarship, bringing people across the gender spectrum together to probe new ideas, perspectives, and possibilities.

This academic year, the center is celebrating its fiftieth anniversary. While marking its past, which includes a vital connection with the New Yorker magazine and a game-changing financial bequest, the center is focusing on current and future issues regarding gender and its intersections with race, sexuality, the arts, politics, ecology, and technology. The program, says center director Sangita Gopal, “imagines the perils and promises of feminist futures.”

Conceived in the early 1970s, a time of roiling cultural upheaval, the early center faced considerable peril—namely, institutional stonewalling and a majority male faculty dismissive of women as a research focus. The center could have remained an unrealized dream except for fortuitous intersections of timing, leadership, and vision.

What if sociology professor and feminist Joan Acker, PhD ’67 (sociology), had backed down in 1971 when the university rejected her request to create an affirmative action program for women? Or when, the next year, every department in the College of Arts and Sciences except her own declined to support her proposal for an interdisciplinary research institute on women? What if she—and the women faculty who coalesced behind her—had been quieter, less focused, less determined?

“Feminism was in the air. And Joan was at the center of it. She was the mother of us all,” says Professor Emerita Marilyn Farwell, who was drawn to Acker soon after arriving on campus in 1971 to teach in the English department.

After her idea for a research institute failed, Acker proposed a scaled-back center within sociology. In 1973, university president Robert Clark approved the Center for the Sociological Study of Women for three years, bestowing it with an annual budget of $5,244.

“She was indefatigable,” says Kate Barry, MA ’81 (sociology), then a graduate student and research assistant at the center. “She was feisty and would take on anybody. She wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

The seed was planted. All it needed was sustenance.

An “obscure” western university

The nascent research center was housed in a small office on the sixth floor of Prince Lucien Campbell Hall, run by graduate assistants and a student secretary with one telephone. It might have remained the runt of university budgeting, underfunded and overloaded, save for another fortunate string of events.

In the late 1960s, Edward Kemp, a librarian with Special Collections and University Archives, had begun collecting manuscripts and materials from women leaders and artists. He found likely sources by reading obituaries in the New York Times.

In 1972 he spotted an obituary for Jane Grant, a feminist, New York Times journalist, and cofounder, with her first husband, Harold Ross, of the New Yorker magazine. Kemp wrote Grant’s widower, William Harris, about acquiring some of Grant’s papers. In their correspondence, Kemp learned that Harris, an editor at Fortune magazine, wanted to fund a women’s studies center at a university but hadn’t found takers who shared his vision. Even Harvard had turned him down.

Kemp met with Harris several times in New York, talking up the work being done at the university’s fledgling women’s research center. Harris agreed to meet with President Clark; before the meeting, Acker and her cohorts briefed Clark on the center’s research and shared “fact sheets on women’s studies at the University of Oregon,” wrote Alletta Brenner, BA ’06 (Clark Honors College, women’s and gender studies), in a 2006 history of the center.

At their meeting, Harris and Clark quickly built rapport; both supported equal rights for women and enjoyed horticulture. They continued to correspond. In 1975, Harris notified Clark that, upon his death, his estate would go to the center.

Harris died in 1981, leaving the center $3.5 million, then the largest bequest the university had received from a single donor. But the funds were temporarily held up by a trustee for Harris’s estate, Brenner wrote, who did not consider the study of women a “real and legitimate . . . form of scholarship,” and was wary of the money going to an “obscure” university on the West Coast.

The endowment was formalized in 1983, assuring the center’s financial independence. The Center for the Study of Women in Society, or CSWS, became one of just two such research centers in the US.

Building research and community

In the ensuing decades, the center—now suitably situated in Hendricks Hall, a former women’s dormitory—has funded hundreds of research projects by faculty, staff, and graduate students.

Some research has focused on local issues, such as a study of the statewide political assault on lesbians and gays in the early 1990s and case studies of women who joined Rajneeshpuram, the notorious religious commune that sprung up in northeast Oregon in the 1980s. Recent research has explored the burdens borne by women caretakers, and how gender and trans issues intersect with race, class, and sexuality. Internationally, the center has funded research on Balkan Romani immigrants, violence against women and girls in Guatemala, and use of social media as a protest tool in Iran.

Among the most influential of center directors was feminist anthropologist Sandra Morgen, who served from 1991 until 2006.

Morgen came into the position with the vision of elevating the center’s identity as a research institution and increasing its impact within the university, the local community, the state, and beyond. She organized signature research projects focusing on women in the Pacific Northwest, nurtured the concept of research interest groups, or RIGs, that bring scholars together to explore specific topics of interest, and forged connections with women’s research centers nationally and internationally.

Morgen died in 2016. In a video presentation at her funeral, Margaret Hallock, former director of the university’s Labor Education and Research Center and founder of the Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics, reiterated Morgen’s guiding principles for center research: interdisciplinary collaboration, intersectional analysis, attention to workers, and political reform and progress. “She wanted research to make a difference in women’s lives, and that it be inclusive and relevant to social transformation,” Hallock said. Morgen and Acker are honored with the annual CSWS Acker-Morgen lecture.

The center also supports performance projects, such as video documentaries, art exhibits, and indigenous theater. Every year, the center awards the Jane Grant Dissertation Fellowship, which provides a year of funding for doctoral candidates to complete their research and writing.

Jenée Wilde, PhD ’15 (English), the center’s information and media specialist, received the fellowship in 2014 for her dissertation on bisexuality in science fiction texts and fan communities. “It was incredible,” she says. “It was the most privileged experience I’ve had to be able to focus on my intellectual work and do it justice.”

Related: Five CSWS Grant Recipients and the Women Who Inspire Them

The center’s embrace of input from across the university keeps it at the forefront of developing issues and administrative or academic gaps within the institution. As a result, several ideas nurtured by the center have evolved into formal programs.

In the mid-2000s, says Lynn Stephen, Philip H. Knight Chair and Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences, there was no focus on Latinx communities and research at the university. In 2008, under the center’s umbrella, the anthropology professor and other faculty members organized a conference on Latinx issues in Oregon and began designing a program. The Center for Latino/a & Latin American Studies, or CLLAS, was approved in 2010 and today funds faculty and graduate student research, celebrates exceptional undergraduates, holds conferences, and curates collaborative projects such as Latino Roots, a two-class sequence in which students produce documentary films used statewide and in a traveling exhibit.

“I feel really grateful for the period in the center that helped incubate CLLAS,” Stephen says. “It’s hard to build something from nothing.”

“These complex and entangled problems must be confronted again—as they have before—with passion, empathy, creativity, and compassion.”

—Sangita Gopal

The center also became a gathering place, initially for women and later for minority faculty who experienced institutional and classroom challenges that cannot be understood by their White counterparts.

The Women of Color Project coalesced in 2008 and “centered around surviving academia and the university as women of color faculty,” says Lynn Fujiwara, the project’s cofounder and first coordinator, who later served as department head of Indigenous, Race, and Ethnic Studies for five years.

Fujiwara’s decision to head the project while on sabbatical “was the most inspiring version of leadership I ever encountered,” says center director Gopal, one of the initial members of the women of color effort. “It was an extraordinary model for feminist mentorship and leadership.”

Today, the project has more than seventy members. It hosts professors and scholars, provides mentoring, and sponsors workshops on writing, research, and creative production. Collectively, the group has brought attention to issues such as the “invisible workloads” taken on by women of color faculty—from mentoring and advising undergraduate students of color to participating on university committees.

“We are called on to [participate in] every diversity mission the university is involved in,” says Gopal. “Those are hours and hours of unaccounted work that don’t come with a monetary reward or contribute to academic promotion.”

Most importantly, says Fujiwara, who is codirecting the project this year, it allows women of color faculty to find each other, create connection, and lift each other up. “Just being able to talk and strategize about situations with people who understand the university and the challenges we face as women of color,” she says. “That is really huge.”

Full of the world, feeling the urgency

Under the banner “Feminist Futures,” the center’s fiftieth anniversary celebration features women leaders in publishing, graphic arts, and avant-garde filmmaking. These cultural pioneers are asking many of the same questions asked by Joan Acker, Sandra Morgen, and the university’s early feminists: who is being denied visibility and respect because of their gender, race, or social status? What perspectives are being overlooked? Whose voices aren’t being heard?

The theme reverberates in upcoming events, including exhibits at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, a panel discussion with former New Yorker editor Tina Brown, and the Lorwin Lecture on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties with Brandeis law professor Anita Hill, an icon of racial and gender equality.

In tune with the anniversary, supporters can give to a $50,000 “Duckfunder” campaign to boost undergraduate learning experiences in gender focused cross-disciplinary research and public-facing writing.

Whatever issues arise in coming years, those questions will be ongoing. The center, says media specialist Wilde, will continue to support research examining gender through a range of interdisciplinary and intersectional lenses. “We are finding ways to show connections that would not normally be obvious,” she says.

Gopal seeks to extend the center’s reach—and resources—into the broader community. She also wants the center to fund undergraduate research and internships. Younger students, she says, “are so full of the world. They feel the urgency of needing to engage with our mission. We need to pay attention.”

In a statement she reads before every anniversary event, Gopal details the challenges facing feminists worldwide: the war on people of color, migrants, refugees, and LGBTQ+ communities. The rise of masculinist nationalisms and the erosion of the rule of law. All against the backdrop of accelerated climate change.

“These complex and entangled problems must be confronted again—as they have before—with passion, empathy, creativity, and compassion,” she says. “And in that spirit of collaboration that is a central tenet of the ethical project of feminism.”

As it has for fifty years, the Center for the Study of Women in Society will continue to light the way—within the university, the local community, and far beyond.

“It is not as though the project of feminism is finished,” says Gopal. “Its horizons are forever open.”

Want to celebrate a Mighty Woman of the University of Oregon? Send us your submission before Women’s History Month in March.

Alice Tallmadge, MA ’87 (journalism), is contributing editor for Oregon Quarterly.

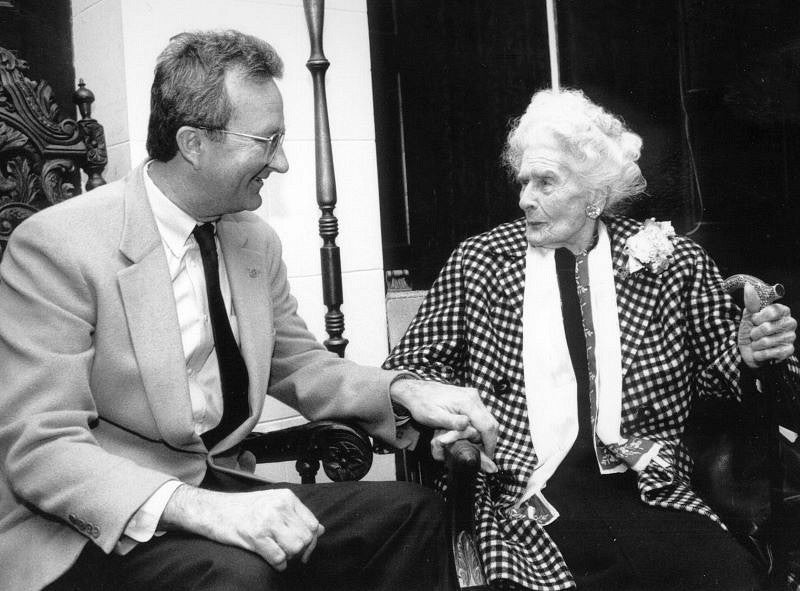

Top Photo: In 1983, campus, community, and noted guests celebrated the opening of the expanded and renamed Center for the Study of Women in Society. Pictured at the November 6 opening celebration, from left, are Barbara Pope, Mavis Mate, Jean Stockard, Marilyn Farwell, Mary Rothbart, Joan Acker, Miriam Johnson, Jessie Bernard, Donald Van Houten, Carol Silverman, Kay McDade, and Patricia Gwartney-Gibbs.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Edward Kemp as Brian Kemp.