Balancing Leather Goods and Sustainability in the Andes

Founders of new lifestyle leather goods company put environment first and emphasize sustainability

By Kelsey Schagemann • Photo courtesy Alta Andina • July 10, 2019

5 min read

Greg Krupa’s wild idea started with a wild animal. A vicuña, to be precise. Herds of these alpaca ancestors roam the mountains of Ecuador, where Krupa, BA ’11 (political science), has lived off and on since 2007. The outdoors enthusiast often spots these long-necked, llama-like mammals on climbing expeditions.

On one such trip four years ago, Krupa couldn’t sleep. “I was cold and uncomfortable, even though I was wearing all this really expensive gear,” he says. “I started thinking about the vicuñas and their fine wool fur and how they sleep easily at high altitude.”

As Krupa shivered in his nylon sleeping bag and polyester sweater, he realized that synthetic materials weren’t keeping him warm. Wouldn’t it be nice, he mused, to wear a sweater of vicuña fur? Wouldn’t it also be great if that sweater could be made locally, and in a way that isn’t toxic to workers and the environment?

“I laid there for hours, wondering why there wasn’t a company making outdoor apparel using natural elements abundant in South America,” Krupa says. “There’s a gap in the market.”

Krupa is closing this gap through his new company, Alta Andina, a maker of lifestyle leather products such as valet trays, coasters, and cardholders. Eventually, he plans to expand into gear for the outdoor enthusiast—leather gloves lined with vicuña fur, for example.

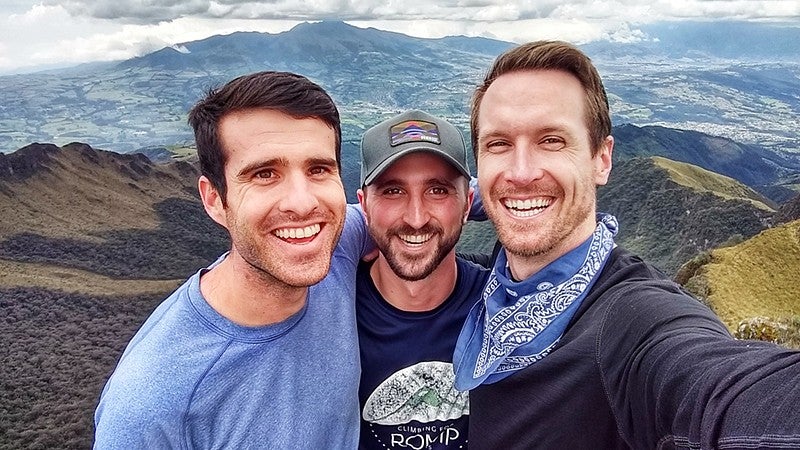

Alta Andina’s founders—Krupa, David Gamburd, BA ’11 (planning, public policy and management) and their friend, Ryan Hood, a graduate of Willamette University—started small to keep their environmental and ethical values at the forefront. This means partnering with local tanneries and manufacturers, as well as using natural materials and environmentally sound production practices.

Protected wild vicuñas in front of the Chimborazo volcano, in the Cordillera Occidental range of the Andes. Photo courtesy of Alta AndinaKrupa and Gamburd met at the UO in 2010, in a planning and public policy course on justice and urban revitalization.

“Greg and I were vocal in discussions and had strong opinions,” Gamburd says. “We felt invested in our education because we wanted to make the world a better place.”

They became closer that summer while canvassing for the Oregon State Public Interest Research Group (OSPIRG), a consumer advocacy group that supports the environment, public health, and economic security.

These topics resonate deeply for Krupa and Gamburd.

Krupa, who grew up in the Chicago suburbs, felt adrift as a student at the University of Kansas. “I had a very narrow view, which was basically ‘me, myself, and I,’” he says. That perspective changed in 2007, after his older brother, David, invited him to Guatemala to work with his nonprofit, the Range of Motion Project (ROMP), which provides prosthetic care to amputees from underserved populations.

Interacting with people who lacked money for food—much less a prosthetic arm or leg—was humbling. Krupa could no longer ignore global inequities.

“Since then,” Krupa says, “I’ve been focused on public health and environmentalism.”

Lured to the UO by his love of the outdoors, Krupa earned his degree and then returned to Guatemala to continue helping marginalized communities there and in South America, in various ways. Among them: Novulis, a mobile dental health company that Krupa founded in 2015 to partner with employers in serving low-income workers and their families in remote areas of Ecuador.

Like Krupa, Gamburd was introduced to global issues through family. Growing up in the Bay Area, he enjoyed frequent outings to state parks and family conversations about the environment. “I remember asking my mom to buy Lunchables,” Gamburd says; she refused, explaining that the plastic packaging was wasteful and the food wasn’t healthy.

The UO was the perfect place for Gamburd to explore his environmental ethos and his passion came through in creative ways. When submitting a research paper on the Great Pacific garbage patch, the vortex of plastic in the Pacific Ocean, he affixed trash—straws and wrappers—to the folder enclosing his essay.

Alta Andina's passport holders are tanned with environmentally friendly tannins drawn from Argentinian, Ecuadorian, and Brazilian trees. Photo courtesy of Alta AndinaKrupa and Gamburd founded Alta Andina in 2017 with a can-do attitude and a focus on environmental stewardship and social entrepreneurship.

Leather goods might not seem like a logical choice for a company with those values, but Alta Andina hopes to educate customers about the toxic global leather industry while protecting the environment. Worldwide, 90 percent of leather goods are tanned using a toxic chemical called chromium, which can cause respiratory and skin ailments for workers. Chromium also leaks into waterways near tanneries, damaging the environment.

Alta Andina leather is tanned with environmentally friendly tannins drawn from Argentinian, Ecuadorian, and Brazilian trees. The cattle hides used for their leather come from the Colombian meat industry—“an otherwise wasted product,” Gamburd says—and Alta Andina doesn’t work with ranchers whose operations contribute to deforestation.

The global leather industry leaves a large carbon footprint. A hide might originate in Brazil before bouncing to Bangladesh for tanning, to China for manufacturing, and finally to the US for retail. Alta Andina shortens this route through its Andean supply chain, keeping those steps within South America until the goods are shipped to the US.

The company’s commitment to the environment also includes conservation and accessibility efforts across the region.

Alta Andina, ROMP, and the Ecuadorian Ministry of the Environment recently signed an agreement to build the world’s highest-altitude, self-guided trail accessible to people with physical and mental disabilities. Located along the continental divide in Cayambe Coca National Park, 14,000 feet above sea level, this quarter-mile trail scheduled to open in 2020 will feature auditory devices, signs in braille, and an elevated walkway.

“The trail’s theme is adaptation,” Krupa says. “The trail will draw parallels between animals and plants that have unique adaptations because they live so far above sea level, with humans who make adaptations when they lose a limb or their sight.”

The trail will also enable hikers to witness what’s happening environmentally as the planet warms. “Snow-capped mountains are less snow-capped now,” Krupa says.

Which brings us back to the mountain-dwelling vicuña. One day, Krupa believes Alta Andina will deliver on its vision to make products with the fur of vicuñas and other animals; the team is developing partnerships and products including scarves, blankets, and apparel.

“This early part of the company is our training wheels,” Krupa says. “We are working in a very patient and responsible manner toward being the first-ever outdoor lifestyle company with products that are 100 percent natural or recycled and come exclusively from South America.”

The trail, if you will, is long. But Krupa is characteristically optimistic, drawing inspiration from the words of John Lewis, the politician and civil rights leader. “If not us now,” he paraphrases,“then who?”

Kelsey Schagemann is a freelance writer and editor in Chicago.