A Campus in Tree Dimensions

Standing at the center of campus history and ecology, our trees help make the University of Oregon truly green

By Jason Stone • Photos and video by Dustin Whitaker • July 3, 2024

9 min read

Trees are essential for defining the character of a university landscape. They delineate open spaces and views, shield unwanted noise, stabilize soils, and cast soothing shade. Seasonal changes in trees provide an ever-changing aesthetic experience, accenting the architectural designs. And trees provide many important environmental benefits; lowering summer energy usage, reducing winter storm-water runoff, and filtering out air pollution year-round.

Woven into the collegiate lore, certain trees help to convey our institutional history. Less often recognized—but no less vital—trees play an important role in supporting human psychology. Research has shown they help reduce the stress associated with urban settings by creating feelings of relaxation and well-being.

In all respects, the University of Oregon is well served by its diverse collection of trees. Along with Ducks sports, good times with friends, and preparation for success in life—when they’re asked to look back on their time here, UO alumni frequently remember our beautiful trees.

“This is a phenomenal place for trees,” Jane Brubaker says.

That’s obvious to even a casual nature lover, but Brubaker is a specialist. A graduate of the University of Oregon’s master of landscape architecture program, she has served as the university’s landscape designer for twenty-eight years. She’s watched the Eugene campus expand and urbanize—but still maintain a verdant, shading canopy of mature trees that is indispensable for visual appeal, ecological health, and human comfort.

“We have these wonderful, green open spaces that are still great for growing trees,” she says. “They’re not confined by concrete; there’s walkways, but not big heat islands. People still tend to think tree roots grow down. But no; they grow out. You can’t plant a big tree in a four-by-four-foot space.”

Arborist and laborer coordinator Becket DeChant, Brubaker’s colleague in Environmental Services, agrees. Having previously plied his trade in urban environments with minimal tree cover—and having closely observed the effects of climate change on trees—he appreciates the green spaces of the Eugene campus and a UO culture rooted in sustainability.

“The greatest gift of working at the UO is seeing how what I’m doing impacts the Eugene campus on a daily basis,” DeChant says. “Generations of people who did my gig before me worked to get us here. We’re just trying to save their work and keep it going.”

The Eugene campus is a ‘de facto’ arboretum and tree-I.D. classroom

Caring for trees

From transplanting and pruning to mitigating root heaves in pavements and maintaining irrigation systems, tree care is a year-round job for the university’s landscape and grounds maintenance crew. Every autumn, just after the new academic year begins, literally tons of leaves drop to the Eugene campus grounds—clogging drains, covering crosswalks, and rendering stairs slippery. Leaves continue to turn and fall through winter.

“From the end of October through March,” DeChant says, “someone is blowing leaves somewhere on our campus.”

More work is on tap in any year—such as 2024—when severe storms blow down branches and topple entire trees. DeChant says clearing the damage from January’s ice storm is “daunting, exhausting, and still ongoing.” He hopes to finish before students return in September.

“So many of the big life events that happen to young people in their college years—whether it’s graduating, getting a job offer, maybe proposing to somebody—there’s a tree that’s attached to that memory.”

—Becket DeChant, arborist with campus planning

Opportunities to plant new trees are welcome, but bittersweet. There’s limited space for additional trees, so most plantings follow removal of mature trees making way for construction.

Informed by nature

Though space for trees is precious today, this wasn’t always the case. When the university opened in 1876, it was shady spots that were in short supply.

“When the campus was first designed and built, there were hardly any trees at all,” Brubaker says. “It was mostly just a grassy knoll.”

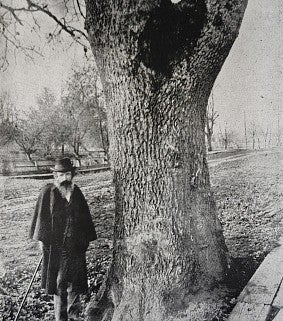

It’s likely the land had been cleared for agriculture during pioneer settlement in the 1850s or ’60s. But two large oak trees were left standing—a tradition of farmers to help maintain soil productivity and provide corridors for pollinators.

Long before the arrival of Europeans, the region’s trees were already being admired, studied, and stewarded. The University of Oregon is located on Kalapuya Ilihi, the traditional indigenous homeland of the Kalapuya people. Drawing upon a deep core of indigenous knowledge, the Kalapuya managed certain trees to maximize production of food, game habitat, and craft materials.

In the twenty-first century, many professional landscapers are reembracing a more ecologically informed approach to creating and maintaining plantings. Brubaker and other project architects have consciously designed many landscapes on the Eugene campus to emphasize Northwest native plants, provide habitats for honeybees and other pollinators, and incorporate the natural processes of decomposition by leaving some dead wood, needles, and leaves on site, rather than maintaining an artificially immaculate environment.

"It’s exciting to have all those design elements in one place: formal landscapes with old architecture and a classic college feel but also try to bring natural spaces and processes onto campus,” DeChant says. “The Eugene campus now stretches from the Willamette River to the South Hills. This is a point of connectivity for many types of wildlife, so it’s important to leave pockets of habitat in the midst of all our buildings and traffic.”

“There’s a big push from our community and our students to plant native things,” Brubaker says. “But honestly, some of our natives are not doing well. We’ve got the emerald ash borer here in Oregon now and it’s going to affect our native ash tree. Western white pine has suffered from a fungus, blister rust. We’re trying to experiment to see what kinds of trees will do well here; we want them to live a long time.”