A Dynamic Approach to Learning Your A-B-C’s

For decades, the UO’s short test has helped millions of kids improve literacy

By Alice Callahan • Illustration by David Gill • April 12, 2023

5 min readAs a doctoral student at Harvard Graduate School of Education in the early 2000s, Gina Biancarosa was working with after-school programs in New York City and looking for a quick, inexpensive way to assess if curriculums were improving students’ reading.

Most options to test reading were costly and took as long as an hour to administer—too impractical and not enough fun for voluntary programs where, Biancarosa says, “students vote with their feet.”

But one reading test caught her eye: DIBELS® or Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, a tool offered by the University of Oregon that is fast to use and free to download, perfect for cash-strapped graduate students and teachers.

The after-school officials “needed something that was very quick, but still reliable and valid, and that was sensitive to instruction or small-grained improvement,” says Biancarosa, now an administrator of DIBELS at the UO and Ann Swindells Chair in Education. “DIBELS really fits the bill for all three of those things.”

For decades, DIBELS has been a standard for testing early literacy, and it is now used in every state to assess millions of elementary and middle school students annually. The short, minutes-long tests published by the UO are based on a simple idea: to test a child’s reading skills, listen to them read.

Validating what grandmothers already know

The idea of DIBELS—pronounced “dibbles”—was to give teachers an easy, efficient way to track students’ acquisition of literacy, says Mark Shinn, a professor in the College of Education from 1984 to 2003. Assessing children while they read was a common-sense approach—“If you want to know how well a kid reads,” he adds, “listen to them read, right? Grandmas knew that.”

DIBELS is based on decades of research that started with Stan Deno at the University of Minnesota in the 1970s and ’80s, says Shinn, who completed his doctoral work with Deno. As researchers at the UO, Shinn and colleagues standardized and validated the short assessments to confirm the tests reliably identified whether children were on track for reading. The original name—DIBS—was coined by Caren Wesson, a faculty member at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee who died of breast cancer in 1994.

“DIBELS gives us consistent data so we’re comparing apples to apples. I don’t know what I’d do without my DIBELS.”

—Gayle Tacchini, BS ’82 (sociology), Willamina Elementary School

For her doctoral thesis at the UO, Ruth Kaminski, MS ’84 (special education), PhD ’92 (school psychology), created short tests to check the reading growth and development of kindergartners and beginning first-graders, says Shinn. She and Roland Good, associate professor of school psychology, later added to these, incorporated several other validated oral-reading tests for older students, and began publishing early versions of DIBELS assessments in the late 1990s at the UO, with the first widely available version published in 2002. Good and Kaminski have since formed their own educational assessment company, but the UO continues to run DIBELS with faculty and graduate student researchers contributing to its continuous evolution.

Out with the old, in with the new

Over the years, DIBELS has been updated multiple times to reflect advances in the science of reading and incorporate feedback from teachers and researchers.

Biancarosa and Patrick Kennedy, PhD ’14 (educational leadership), a senior research associate in the college’s Center on Teaching and Learning, led a complete revision of DIBELS for the current eighth edition. They dropped less useful measures, added a measure of word reading, extended the grade range of some measures, and incorporated all new reading passages. Regional-specific references such as “butte” have been removed and the passages are more relatable to children in urban areas and with more diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Schools typically administer DIBELS assessments three times per year. Depending on grade level, the tests require no more than five to seven minutes per student to administer. New rules in the eighth edition allow for stopping the assessment if students are extremely successful or unsuccessful on the measures, saving even more time for instruction.

Checking reading “vital signs”

Just as you have your blood pressure and temperature checked at every doctor’s visit, DIBELS are meant to be basic screening assessments, Biancarosa says.

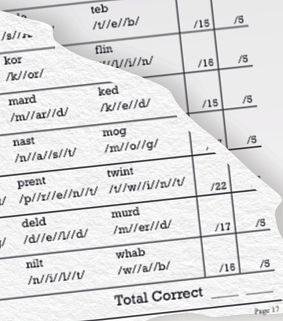

For example, during a DIBELS assessment, a first-grade student might be asked to read the names of letters from a mixed-up list (“t, n, P, L, e,” and so on); then to sound out “nonsense” words (“tib, yate, lish, thamp”); next, to read from a list of common but increasingly difficult real words (“no, they, there, help, island”); and finally, to read a passage from a story (“Bobby was on his way home from school one day . . . ”). All the while, an educator listens and tracks how much the student can successfully read on their own.

If a student scores below their grade-level benchmark on one or more measures, that’s a signal they may need specific interventions to catch up. For these students, DIBELS assessments can also be given more frequently to see if the extra instruction is helping, just as a patient with high blood pressure might be monitored to see if they’re responding to changes in diet or a new medication.

At Willamina Elementary School, in a rural, predominantly low-income district east of Salem, DIBELS has been a key tool in the reading program for more than a decade, says reading specialist Gayle Tacchini, BS ’82 (sociology).

With DIBELS, Tacchini and her team have systematically identified which kids need more intensive instruction, leading to dramatic improvements in reading. When they started using DIBELS, about 25 percent of students were reading at grade level, and just before the pandemic, about 75 percent were hitting that goal. The disruptions of the pandemic rolled back some of those gains but now DIBELS is helping Tacchini track students’ progress in catching up.

“What DIBELS does is it gives us consistent data, so we’re comparing apples to apples,” she says. “I don’t know what I’d do without my DIBELS.”

Alice Callahan is a freelance writer in Eugene whose work appears in publications including the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Knowable Magazine.