Religious Scholar Courts Controversy with “Creating the Qur’an”

Stephen Shoemaker challenges claims adopted by Muslims and non-Muslims alike

By Sharleen Nelson • August 17, 2023

5 min read

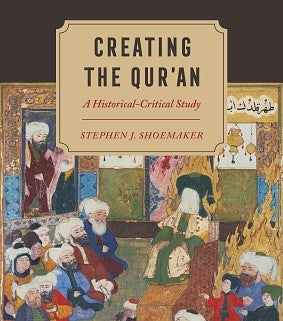

When Stephen Shoemaker set out to write Creating the Qur’an: A Historical-Critical Study, a book exploring the origins of the Qur’an, he was aware it might be controversial, but the University of Oregon professor approached it the way he would any other text—through unbiased research based on scientific methods and historical evidence.

One of only a handful of scholars to attempt to unlock the puzzling origin of the Qur’an, believed by Muslims to be a literal transcript of God’s speech, Shoemaker challenges traditional claims adopted by Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Because Islamic tradition has historically defined the text and controlled its interpretation, the book fuels scientific debate—and controversy—concerning the authenticity, historicity, and canonization of the Qur’an.

Offered as an open-access publication, the 2022 book can be downloaded free from University of California Press. A Kindle version is also available on Amazon.

Professor Shoemaker is the Ira E. Gaston Fellow in Christian Studies in the Department of Religious Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences. He defines religious studies as a historical analysis of how religions developed in terms of culture, politics, economy, and literature.

But when its focus is Islam, emotions can run high.

Last year, for example, author Salmon Rushdie was on stage to speak in New York when he was attacked by a supporter of the radical group Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. In 2015, Muslim extremists forced their way into the offices of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, killing twelve people and injuring eleven others for publishing cartoons of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

In publishing Creating the Qur’an, Shoemaker says, “people jokingly asked if I’ll start wearing a Kevlar vest to work.” But he notes the only real pushback has been from academic colleagues, mainly Islamic scholars, in nonviolent ways.

“There seems to be a reluctance to allow these kinds of critical questions,” Shoemaker says. “But if we’re going to have a discipline of religious studies, we must study religion ‘critically’ as part of the secular academy, and we have to do it in a way that treats all religions on an equal basis and asks the same questions and expects the same things in terms of evidence.”

Shoemaker is also the author of The Death of a Prophet, The Apocalypse of Empire, and A Prophet Has Appeared, among other publications, and he is presently working on a short historical study on the life of Muhammad.

In Creating the Qur’an, he approaches the central Islamic text as a historical artifact, examining every significant controversy about the Qur’an, its history, and its canonization by studying historical documents, applying advanced scientific methods, and researching the linguistic history of Arabic and the social and cultural history of the late ancient Near East.

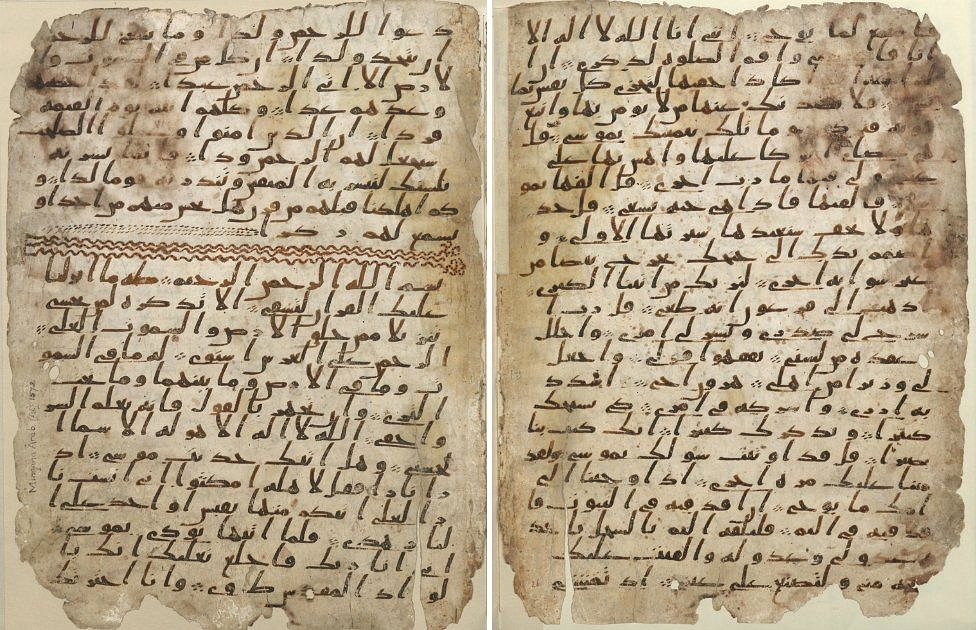

One question is the age of the Qur’an. Shoemaker and other scholars have turned to radiocarbon dating in search of an answer. Developed in the late 1940s, radiocarbon dating, or carbon-14 dating, is a method to determine the age of organic materials as old as sixty thousand years. Attempts have been made to date the parchment (made from animal hides) of several early Qur’anic manuscripts, but so far, the method has proven unreliable for establishing the precise time frames that scholars seek.

“Radiocarbon dating is fantastic if you want to date something to a century or two. If you want to see if an object is late medieval or early medieval, radiocarbon dating is your best method. It’s rock solid,” he says. “The problem comes if you want to date something to 650–670 CE. The method can’t do that with sufficient accuracy. It might give you some data that you like, but in the end, you have to be really cautious when you’re trying to get that narrow.” Shoemaker concluded that the canonical text of the Qur’an was most likely produced around the turn of the eighth century.

Likewise, because most of Muhammad’s teaching was not initially written down, the early texts that became the Qur’an were transmitted for decades from memory and by oral tradition. Shoemaker’s research highlights that memory, compared to a written record, is unreliable. For instance, research in memory science has demonstrated that verbatim recall of a text of more than fifty words is beyond the capacity of human memory, absent a written text.

“This book was personally the most edifying book I have ever written. I learned so much about myself working on the chapters on memory.”

“People remembered these important texts later on in ways that highlighted the importance of the text for their present circumstances rather than recalling what really happened,” he says. “Historians are always looking for probability. We can’t definitely say what happened, but we can say that ‘this’ is a lot more probable than ‘that’ is.”

“This book was personally the most edifying book I have ever written,” Shoemaker says. “I learned so much about myself working on the chapters on memory. I’m more attuned to memory as a sort of defining quality of human existence and how it works and how it doesn’t work and why it works the way it does.”

The book is not required reading in Shoemaker’s Religion 102: World Religions: Near Eastern Traditions, an undergraduate course on the history of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. But critical examination of all religions equally, he says, is as fundamental to the classroom as it is to scholarship.

Sharleen Nelson, BS ’06 (journalism: magazine, news editorial), is a staff writer for University Communications.