She Risked Everything for Women, Workers, and Justice

Alumna Marie Equi was a homesteader, doctor, and activist in the early twentieth century

By Ed Dorsch • Illustrations by Audra McNamee • January 17, 2024

5 min read

A “firebrand in the causes of suffrage, labor and peace.”

—Oregonian, July 15, 1952

A graduate of the University of Oregon Medical School, Marie Equi was a homesteader, activist, lesbian, mother, and physician. Throughout her courageous life, she fought for labor reform, free speech, women’s suffrage, family planning, fair wages, and peace.

Equi was born in 1872 to immigrant parents in New Bedford, Massachusetts, one of eleven children (three siblings died young). She began working in a textile mill after her first year of high school. Her partner Betsey Bell Holcomb paid for Equi to attend seminary, but the money ran out after one year.

At age twenty, she travelled three thousand miles to join Holcomb on an Oregon homestead. The couple collected water from a stream and tended a two-acre garden. Unlike many before them, they completed the requirements of the 1862 Homestead Act that allowed them to keep the land: cultivating five acres and living on their land for five years.

As two young, single women living together in the small community of The Dalles at the turn of the twentieth century, Equi and Holcomb drew considerable attention. But Holcomb’s teaching position at a private school helped them gain acceptance.

When superintendent O. D. Taylor repeatedly refused to pay Holcomb in full, Equi’s fiery temper got the best of her—and him. Accounts of Equi threatening Taylor with a horsewhip, surrounded by curious onlookers, were published in newspapers as far away as Portland and San Francisco. One story declared, “She is queen today.” Following the fracas, locals raffled off Equi’s whip, giving the proceeds to Holcomb. Taylor was later arrested for crooked real estate dealings.

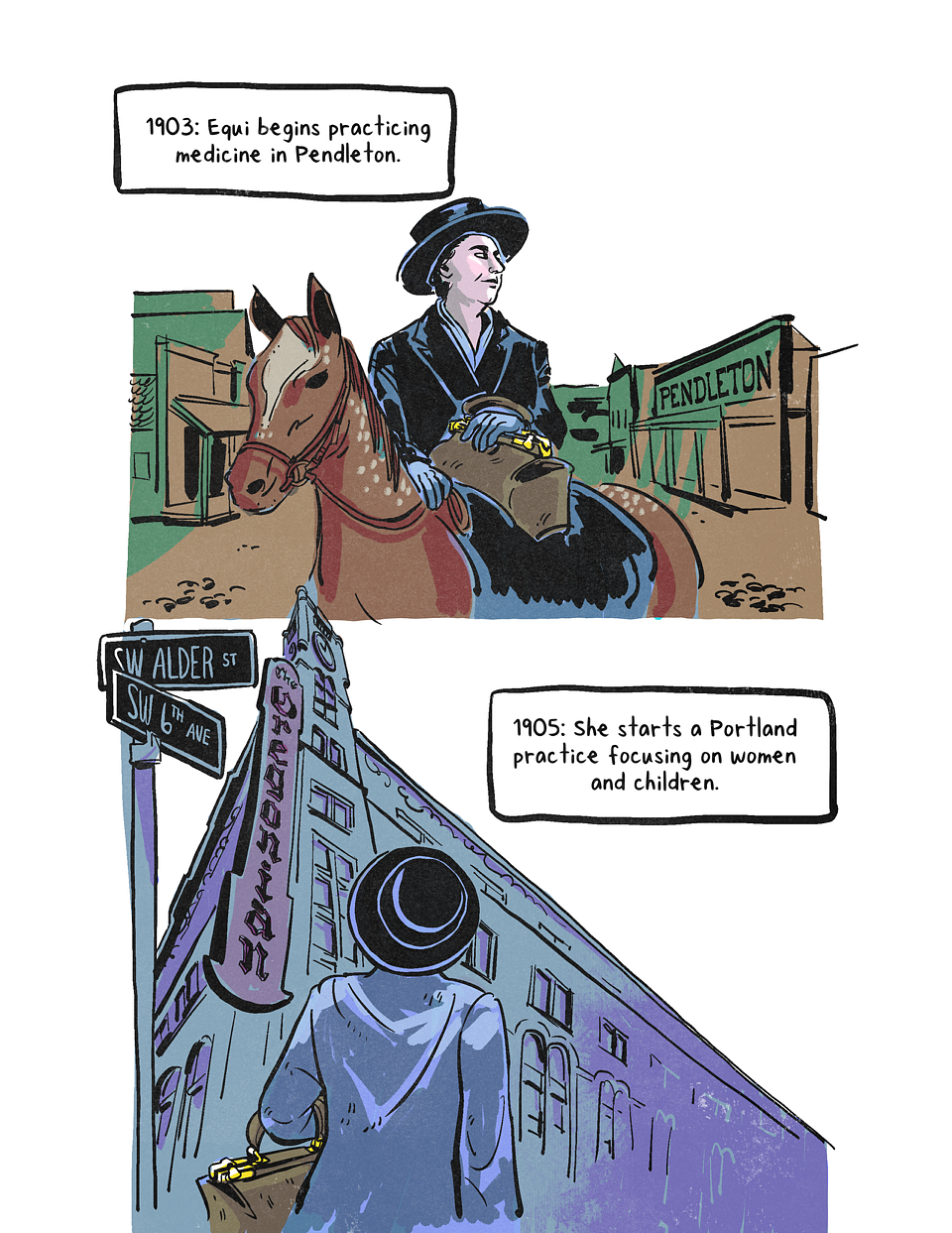

Sixteen years after dropping out of high school to work in a textile mill, Equi graduated from the UO medical school in 1903. She began practicing medicine in Pendleton, where she often travelled by hours on horseback to treat patients.

She later opened an office in Portland’s first skyscraper, emphasizing obstetrics, gynecology, and maternal and childhood health. Because of her background, Equi had an excellent rapport with her working-class patients. But she was also comfortable in upper-class social circles. By charging full price for wealthier patients, she could offer free care or reduced rates to those who had less. Though it was illegal, she also provided abortions.

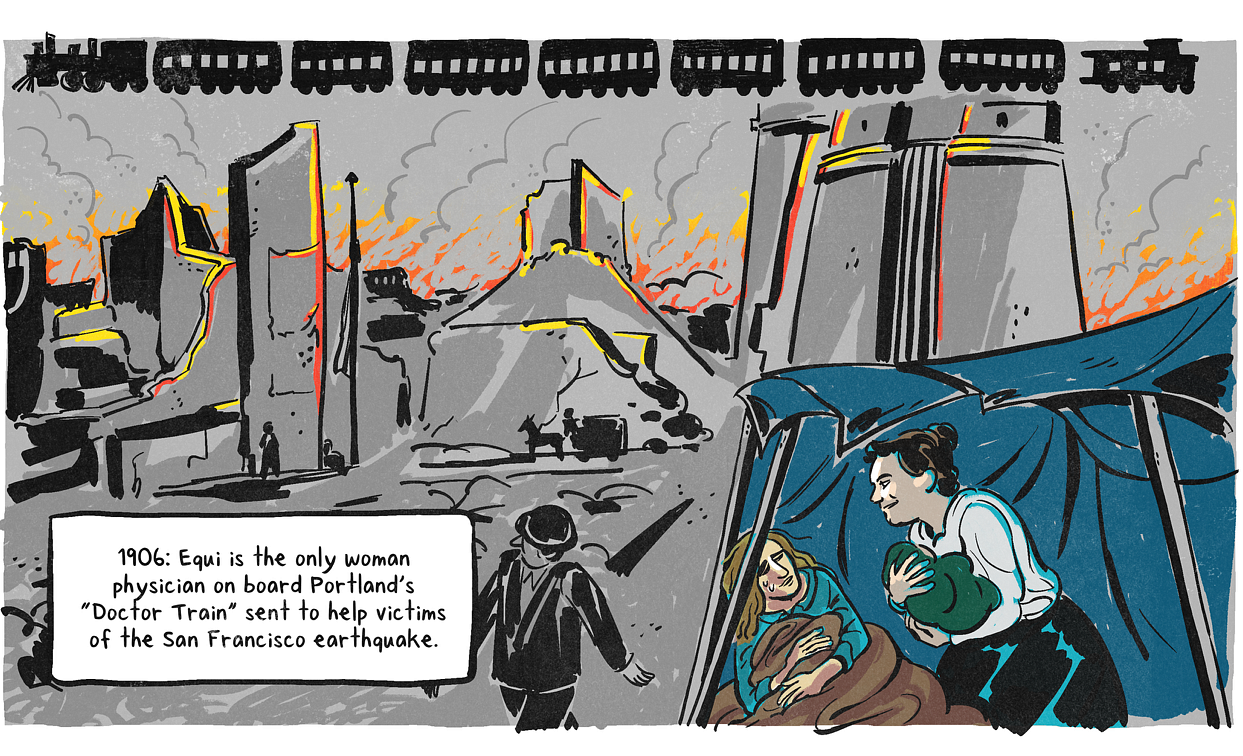

The great San Francisco earthquake and fire hit April 18, 1906, and the “Rose City” rushed to help. The day after the disaster struck, Portland doctors, nurses, and volunteers—and tons of donated medicine, food, clothing, and supplies—headed south on the so-called Doctor Train. Equi, the only woman physician in the group, was appointed head of obstetrics at the US Army General Hospital in the Presidio. Twenty-three children were born in what came to be called the “Oregon Ward,” and the army gave Equi a medal and commendation.

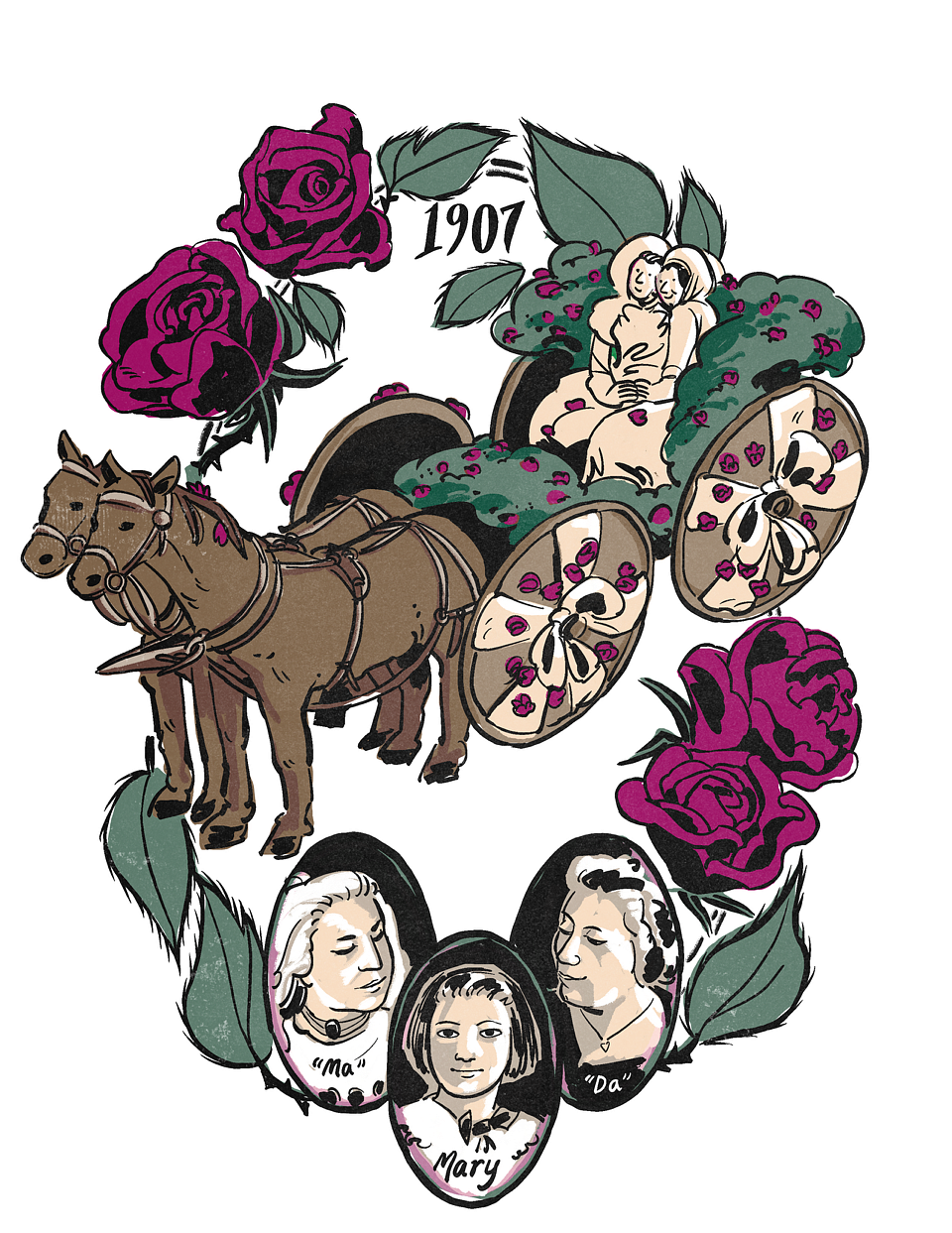

On June 22, 1907, Equi and her partner, Harriet Speckart, took second place in the carriage-and-pair category of the Grand Floral Parade, an event during Portland’s first Rose Carnival and Fiesta. In 1915, the couple adopted a three-week-old girl, Mary Jr., who called Equi “Da” (for “Doc”) and Speckart “Ma.” At sixteen, Mary became Oregon’s youngest woman pilot.

A leader for women’s suffrage, Equi was among the first women in the state to register to vote and to serve jury duty. Like many Portlanders of her era, she supported fair wages, family planning, education, and other progressive causes. However, Equi’s activism took a radical turn in 1913.

When she noticed former patients among striking women cannery workers on Portland’s east side, she heeded their pleas for help. Her speech calling workers to join the strike led Equi to join in picket lines and scuffles with police—and arrests. Equi went on to support more causes (and serve more jail time).

Portland celebrated National Preparedness Day with the largest parade in city history. In protest, Equi decorated her car with a US flag and an antiwar banner, snuck into the parade, and was attacked by participants—then arrested. Later that month, Equi and activist Margaret Sanger were arrested for selling copies of Family Limitation, a pamphlet about birth control that Equi helped edit. But it was her fervent antiwar speeches that landed Equi in prison for ten months under the 1918 Sedition Act. She was later pardoned by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“I’m going to speak where and when I wish. No man will stop me.”

—Marie Equi

When Equi died in 1952, the Portland Longshoremen’s Union passed a resolution declaring her an “outstanding fighter” who “braved personal danger and hardships to preserve peace, freedom of speech, and the right of labor to organize.” In 2019, a bronze plaque celebrating Equi was added to San Francisco’s Rainbow Honor Walk. A mural installed in the UO’s Erb Memorial Union in 2023 features a portrait of Equi.

Want to celebrate a Mighty Woman of the University of Oregon? Send us your submission before Women’s History Month in March.

Ed Dorsch, BA ’94, MA, ’99 is a staff writer for University Communications.

Audra McNamee, BS ’22 (mathematics and computer science), is a nonfiction cartoonist living in Portland, Oregon. To learn more, visit audmcname.com.

Special thanks to Michael Helquist, a San Francisco author, historian, and journalist who generously provided consultation for this story. To learn more about Equi's extraordinary life and Portland's Progressive Era, read his book, Marie Equi, Radical Politics and Outlaw Passions.