Timber workers and environmentalists: Steven Beda Examines Historic Conflict

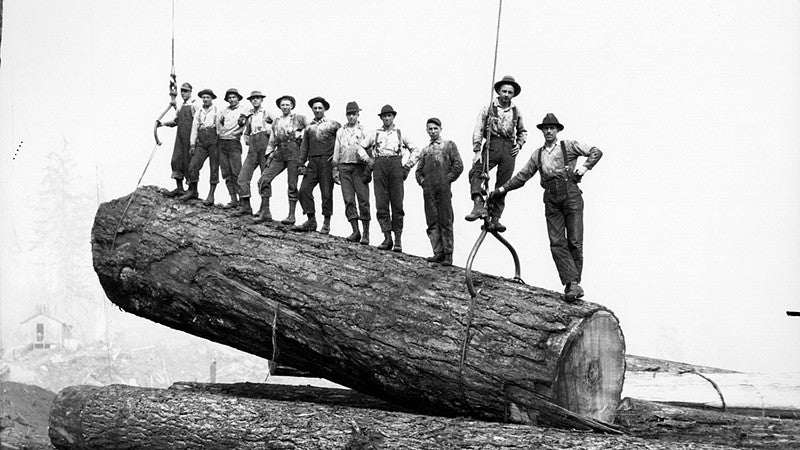

By Emily Halnon • Photo courtesy University of Washington Libraries Special Collections • January 21, 2020

4 min read

As Steven Beda was fishing for steelhead and salmon over the course of a few recent seasons, he caught onto an unexpected pattern in the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

The University of Oregon assistant professor of history kept encountering timber workers who also ventured into the woods to fish, hunt, and enjoy the outdoors. As they traded small talk, Beda noticed the loggers discussed nature and the wilderness in a way that was very similar to that of environmentalists.

“We’d start off talking about whether the fish were biting and as we chatted, they kept emphasizing the aesthetics of the forest and their desire to protect it,” he says.

Beda was surprised, as it countered narratives that have associated loggers with clear-cut hillsides and clashes with environmentalists—especially in recent decades, as the groups battled over issues such as protections for the Northern spotted owl and its habitat in old-growth fir trees.

Beda, who specializes in labor and environmental history, realized there was an opportunity to turn these riverside chats into a research project. He started examining how loggers have shaped nature over the past century, and how nature has shaped their politics and values.

Beda will publish his findings in Strong Winds and Widow Makers: A History of Workers, Nature, and Environmental Conflict in the Pacific Northwest Timber Country, 1900 to Present. In this account, still being scheduled for release, Beda turned to archives, timber union documents, memoirs, and interviews to explore these workers’ relationship to the forest and to ask how it has influenced their ideas and political actions.

His findings aligned with what he’d been hearing in the woods. He discovered that timber workers have a long and proud history of environmentalism and have helped advance landmark legislation and initiatives that preserved large swaths of forest and wilderness—including the 1964 Wilderness Act and the establishment of the Three Sisters Wilderness and Olympic National Park.

“Protecting the environment was and remains central to the identity and activism of timber-working communities,” says Beda. “The forests are part of who they are, places they’ve cared for as deeply as any friend or relative, and something they’ve fought to protect for deeper cultural reasons.”

It’s actually not all that surprising if you think about it, muses Beda. Timber workers are among the individuals most embedded in the forest—for both work and play. And if you spend nearly all of your days surrounded by colossal evergreens, forest floors blanketed in lush moss and ferns, and cobalt rivers charging through wild landscapes, it’s probably natural to develop a deep-seated affinity for the outdoors.

Timber workers’ meaningful relationship with the forests dates back generations, like many circles of tree rings. It’s rooted in the beginning of the 20th century, when most timber workers lived in remote logging camps and company towns. Their bare bones, one-room shacks were encompassed by expansive forests that were a source of employment, sustenance, and recreation for them and their families.

Interviews and memoirs from this period reflect a deep love and appreciation for nature, with many references to camping, hunting, fishing, and just whittling away any free time outside.

“It was clear that their connection to the landscape ran much deeper than jobs,” Beda notes.

It was this sentiment that motivated workers to leverage their union—the International Woodworkers of America—to protect forests, in addition to their jobs, in the mid-20th century. The union helped workers partner with wilderness groups such as the Sierra Club to lobby for more land protections—even those that their employers opposed, like the Wilderness Act, which preserved 9.1 million acres of federal land.

Timber workers have always seen the forests as a source of jobs and economic opportunity, of course, Beda says, but it’s about balanced forest management.

“They see the forest as a place for work and economic security,” he adds, “but they also want to protect their access to the wilderness for recreation and to preserve its ecological health.”

Timber workers felt that balance go askew in the second half of the 20th century, which caused them to shift away from their environmentalist allies.

During the 1980s—when the spotted owl conflict emerged—the shared values of these groups were strained to the breaking point as environmentalists sought protections from sweeping logging projects and, as a consequence, timber workers faced the loss of tens of thousands of jobs.

The demographics of environmentalists had also been shifting since the 1960s, as rural Americans with a kinship for timber workers were increasingly outnumbered by city dwellers inspired by the aesthetics of the nature they absorbed during weekend backpacking escapes. But many of the new environmentalists failed to acknowledge that lumber was providing them shelter and warmth back home, Beda says.

Since then, the groups have remained more antagonistic than unified on most issues. But Beda notes the tensions between loggers and environmentalists are a recent development and the groups share a long history of working together to protect the environment.

Timber and the Wilderness Act

Last year marked the 35th anniversary of the Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984, under which Congress preserved 8.2 million acres of federal lands following environmental lawsuits brought by Neil Kagan, JD ’81. In the article Wilderness, Luck and Love: A Memoir and a Tribute, he recounts this history, the links between activism and legislation, and a love story about the woman vital to the prosecution of the lawsuits.

Emily Halnon is a staff writer for University Communications.