Tiny Worms and Time Machines

Innovation in gene editing could speed better understanding of human diseases and development of new drugs

By Laurel Hamers • Illustration by David Gill • April 12, 2023

3 min read

Traveling through space and time like Doctor Who might still be beyond the scope of current Earthly science. But University of Oregon biologists are bending time in their own way, via a new gene-editing technique that compresses years of work into days.

They’ve named their new technique “TARDIS”—a playful nod to the time-and-space traveling police box from the classic British sci-fi TV show.

Working in worms the size of a pinhead, the UO team has found a way to test thousands of genetic mutations in one fell swoop.

The advance will make it possible for biologists to quickly do experiments that compare many versions of a gene, hunting for mutations that lead to specific traits. Such research is often a crucial first step toward unraveling the mechanisms behind human diseases or finding new therapeutic drug possibilities.

By speeding up a part of the process that’s currently painstakingly slow, the advance makes new kinds of experiments possible in animals.

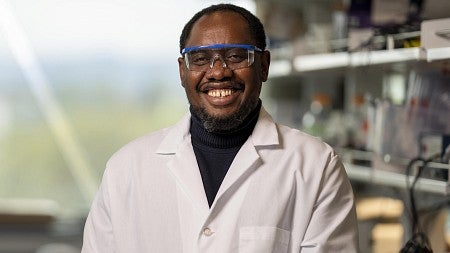

“In biology, we spend a lot of time working with genetic mutants. But in animals, we’re limited by how many genetic mutants we can make at one time,” says Zach Stevenson. Stevenson, a graduate student, helped design the technique with research professor Stephen Banse, BS ’03 (biology). Both work in the lab of Patrick Phillips, a professor in the Department of Biology in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Today, scientists can make precise, targeted genetic mutations in animal subjects such as worms or fruit flies. Still, each subject with a different combination of genetic mutations must be engineered individually. It can take months to make all the mutant strains for an experiment.

The new technique, says Stevenson, “is a way around that bottleneck.”

Comparing the effects of many genetic mutations simultaneously is a key starting point for many questions in modern biology.

For example, consider a scientist who hopes to identify a mutation that makes people less susceptible to the effects of a strain of deadly bacteria.

She might start by testing how hundreds of worms, all with different genetic mutations, react to the bacteria. She could then single out the ones that survive for further research—something in their genes is protecting them. These screening experiments narrow down the possibilities and help scientists figure out where to focus time and attention when translating that knowledge to human-based studies.

With the new method, Stevenson says, “for the same labor of making three or four mutations, you can make tens of thousands.”

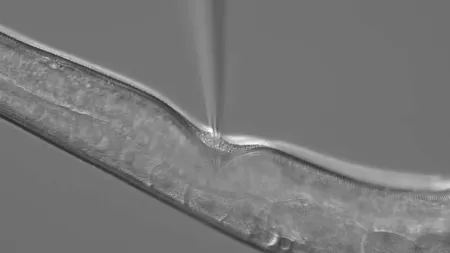

The team has piloted the technique in C. elegans, a tiny worm that’s popular for biology research. A similar approach could eventually be used on other research animals.

While mass gene-editing is frequently used in single-celled organisms such as bacteria and yeast, the Phillips team is the first to make it possible on this scale in an animal.

The new approach works by compressing the information needed to make many mutations into a single package, which is engineered into an individual worm. When that worm reproduces, its offspring each have different mutations, saving researchers the time of editing the genes of hundreds of worms individually. (For details on the new technique, see this related story.)

Here, TARDIS stands for Transgenic Arrays Resulting in Diversity of Integrated Sequences. Like the famous fictional TARDIS, the worm “is bigger on the inside,” Stevenson says—it contains a lot of extra genetic material in the same small package.

The team sees broad applications for biology in general, doing experiments that before were only possible in yeast or bacteria, Banse says. “Now we can do these things in an animal model.”

Laurel Hamers is a senior writer and editor of science and research communications for University Communications. She has been a science writer and editor for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, was a reporter for Science News magazine, and has held positions at the American Institute of Physics and the San Jose Mercury News.