Fusing Art and Science to Save the Seas

At the forefront of blue humanities, Stacy Alaimo explores the intersection of aesthetics and marine conservation

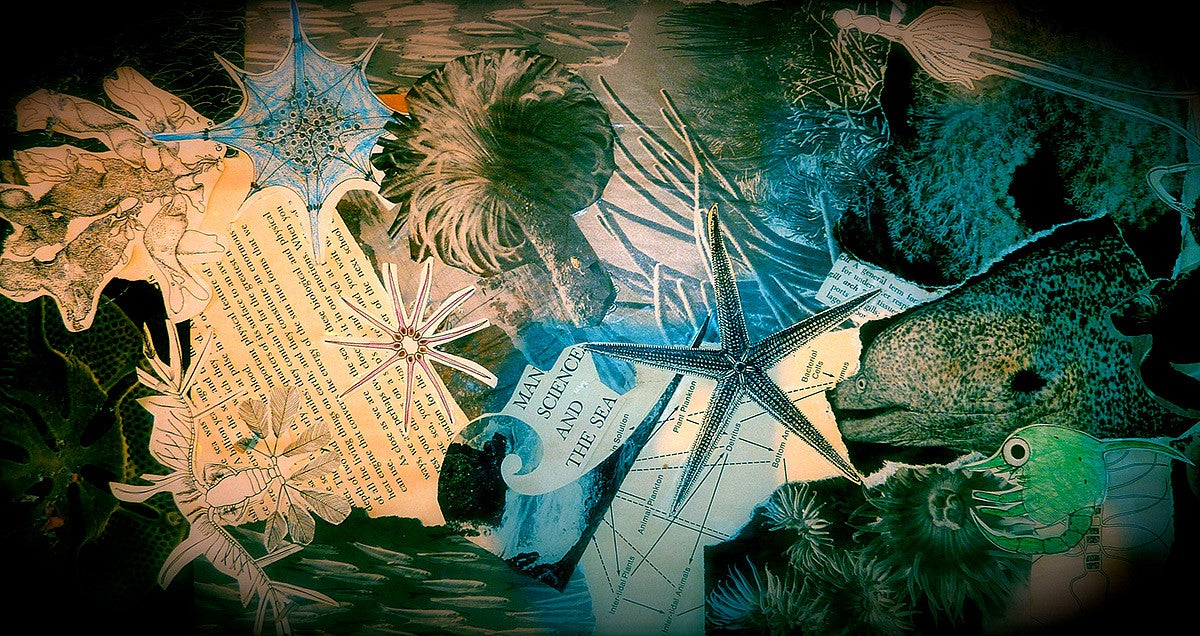

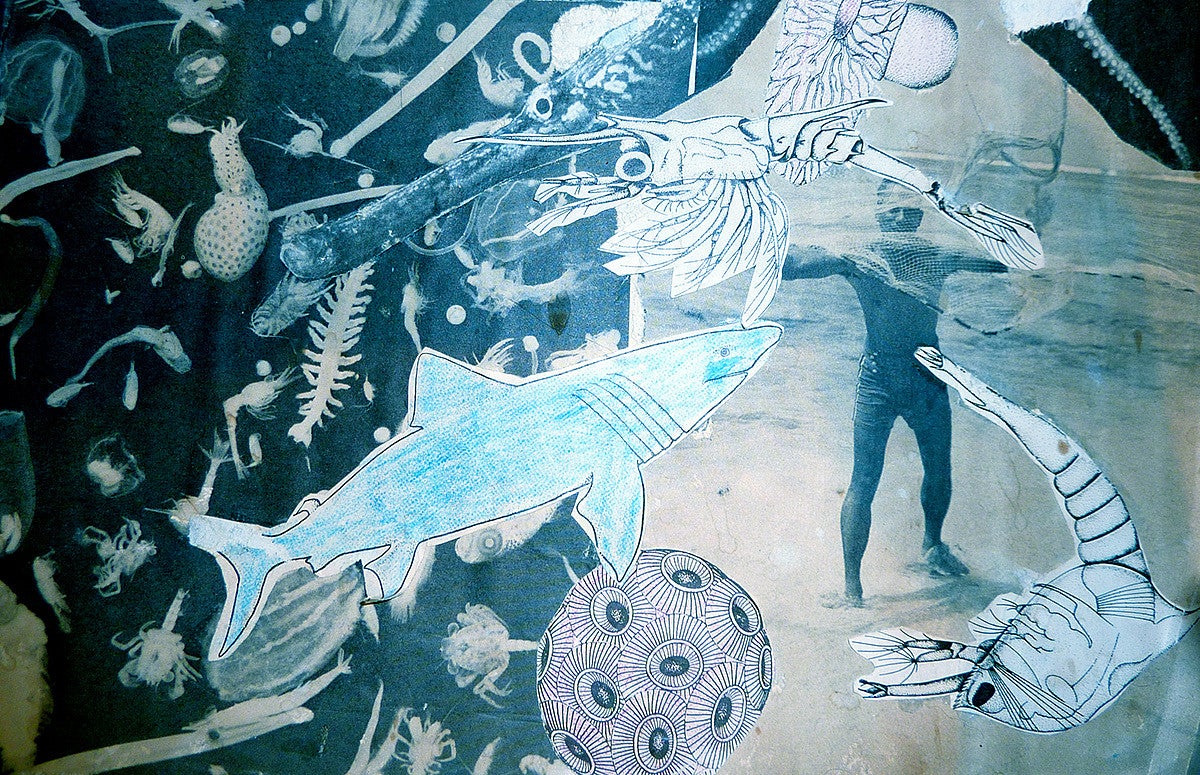

By Lauren Hodges • Illustration by David Gill • April 12, 2023

3 min readIt’s said some of Hollywood’s most famous monsters were inspired by creatures that live in the darkest reaches of the ocean.

This presents Stacy Alaimo with an intriguing conundrum for conservation efforts. “Deep-sea creatures are often pictured as aliens from another planet, and that gets people interested in them because we’re all interested in novelty and weirdness and the surreal,” she says. “But the idea of the alien can also cut us off from any responsibility.”

Alaimo is a professor in the Department of English and the Environmental Studies Program, both in the College of Arts and Sciences. She is also a leader in blue humanities, combining the critical study of the human world with marine science and ocean ecologies.

In her new book, Deep Blue Ecologies: Science, Aesthetics, and the Creatures of the Abyss, Alaimo explores an idea based in her fusion of art and science: how do aesthetics affect conservation efforts?

Presenting images of deep-sea creatures as unrelatable animals promotes a detached world absent of our inflictions on the planet and therefore not requiring conservation, Alaimo says. She is examining the dichotomy of photographing marine creatures in a way that promotes conservation without reducing them to “pretty pictures” devoid of context.

“I always try to work from a place where I can’t figure it out conceptually, ethically, politically,” Alaimo says. “I always try to go to the spots that are really difficult and that’s where I think the work happens.”

Sea creatures and social justice

Alaimo also explores images of marine life through the lens of social justice and colonialist concerns. “One of the things I am interested in is the idea of who the spectator is, who is the ‘we,’” Alaimo says. “When these images of deep-sea creatures are circulated, it is another kind of colonialist vision. How can I be concerned about these fish across the world in the deep seas that aren’t part of my life?”

Drawn to Jacques Cousteau and William Beebe

Alaimo watched The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau as a child. But it was naturalist William Beebe of the early twentieth century who inspired her work at the intersection of science and the humanities.

“Beebe was in this moment where science was starting to become modern, which meant objective, disconnected, not related to the arts or humanities,” says Alaimo. Beebe sought to connect how the beauty of a creature relates to conservation, for example.

Dance of the manta rays

Alaimo began scuba diving while in graduate school.

Her most memorable experience was a night dive in Hawaii: “We’re sitting at the bottom, and we have a little flashlight pointed up. And then giant manta rays came right at us with this big mouth, and then at the last second, they gracefully arched back and came back around—like ballet dancers. That was one of the most beautiful, moving moments of my entire life, these manta rays in this beautiful ballet.”

Lauren Hodges, an environmental science major and member of the class of 2024, is a staff writer for the Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation.