“Live Well, Think Beautifully”

Undergrad anthropologist immerses himself with an Indigenous people who are determined to protect their way of life

By Matt Cooper • Photos courtesy Rowan Glass • June 9, 2023

11 min read

It was the murder of a shaman that illustrated to Rowan Glass the fortitude of Indigenous peoples.

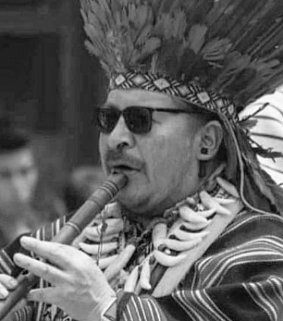

He was eighteen and backpacking in southwest Colombia in 2019 when he met Miguel Ángel Muchavisoy, renowned shaman of the Kamëntšá people, who live in the Sibundoy Valley, a lush basin between the Andean highlands and the Amazonian lowlands. Glass sought to experience yagé, a potent hallucinogenic brew sacred to the Kamëntšá for what they regard as its medicinal and spiritual powers. The bespectacled Muchavisoy, an experienced shaman and former elected official, agreed to guide Glass through a typical ceremony with the drink, which can cause crippling nausea and intense visions.

Glass eventually opted against the ceremony but befriended Muchavisoy. He was devastated to learn, in 2021, that Muchavisoy had been gunned down in his home by two attackers from outside the community. Possible motives, according to news reports, included money, revenge for a death that happened during a previous ritual led by Muchavisoy, or even politics, given the leader’s standing as an Indigenous activist and organizer in one of the world’s deadliest countries for defenders of human rights and the environment.

Regardless of the truth, Glass—by then a junior anthropology major at the University of Oregon—saw the shooting as the latest offense in a centuries-long intrusion by outsiders into the world of the Kamëntšá. And the stubborn survival of the Kamëntšá way of life despite this history inspired him to study how the people preserve and renew their culture to protect who they are.

“Nearly five hundred years of colonial dispossession have not succeeded in stripping the Kamëntšá of their unique culture, language, and thought,” Glass says. “The murder of Taita Miguel served as the catalyst to better understand a people that remain, against all odds, vibrant and resilient today.”

Colonialism, mining, a language on the brink

Archaeological evidence suggests the Kamëntšá—pronounced “come-CHAH”—and their ancestors have been in the Sibundoy Valley since around the year 600, and perhaps much earlier. Their way of life intertwines nature and spirituality with shamanic rituals and plant-based medicines, an ancestral solar god and lunar goddess, and a sacred connection to their land, which they call Tsbatsána Bebmá, or Mother Earth.

Spanish conquistadors ushered in sporadic violence against the Kamëntšá beginning in 1535. But it was the Capuchin Catholic missionaries of the 1900s—come to “civilize the savages,” in their words, and infamous for whippings and other forms of torture—that threatened the group’s very existence. Their land was taken, their customs violently discouraged, their children punished harshly for speaking their native language.

The harms of twentieth-century colonialism have given way today to the pressures of globalization: mining and oil drilling projects that contaminate the drinking water, highways planned through Indigenous land and ecologically sensitive areas, sweeping agricultural projects on property that once hosted the small medicinal-nutritional gardens that were a cornerstone of every household, and an influx of non-Indigenous settlers who now outnumber the Kamëntšá.

“The Kamëntšá people show a resilience and adaptability

that all so-called marginalized and oppressed peoples are capable of.”

And yet the Kamëntšá survive, and fight back. Their numbers are holding steady at seven thousand, according to Glass, and they’ve reclaimed large swaths of land with legal protections. Protesters stopped a road project by marching on the regional capital. Muchavisoy’s death was met with outrage and a demand for justice from the state.

One ongoing concern is the vanishing Kamëntšá language, spoken by just a fraction of the population. The language is critical, Glass says, because it underpins the Kamëntšá “thought system”—values around family, nature, reciprocity, ancestral wisdom—which in turn inspires them to defend their culture and territory. One popular Kamëntšá saying: “Live well, think beautifully.”

“We have to wake up”

From the time of his arrival on the UO campus in fall 2021, Glass—who transferred from Portland Community College with an associate’s degree and two years remaining for a bachelor’s—began contemplating topics for a senior thesis in anthropology, which is part of the College of Arts and Sciences. A second visit to the Kamëntšá in summer 2022 and a third in February inspired him to examine how this community is fighting for its way of life through reclaiming ancestral land and renewing—or reimagining—cultural practices.

Says Glass: “It is no longer self-evident to suggest that Indigenous cultures are doomed to annihilation by the relentless growth of global capitalism and Western cosmopolitanism. The Kamëntšá people show a resilience and adaptability that all so-called marginalized and oppressed peoples are capable of.”

Glass found, for example, that Kamëntšá artisans have begun to embrace beadwork for bracelets and necklaces due to the low cost of materials and ease of production, which increase profitability. But he doesn’t see the practice as a break from the Kamëntšá tradition of weaving; the beadwork features the same age-old and meaningful motifs—the sun, the territory, the womb—and its popularity with younger craftspeople, he says, helps sustain and extend the crafts practice to the next generation.

For his research, Glass explored the importance of jajañ gardens for nutritional, medicinal, and spiritual sustenance. He attended the annual festival of Bëtsknaté, during which thousands fill the streets to celebrate and renew the culture with crafts, music, dance, and ceremonies. He interviewed Kamëntšá people ranging from teens to those in their eighties, capturing a kaleidoscope of opinions on issues including colonialism, environmental degradation, and the future.

“The radical Indigenous groups that think that everything is ours, that the other is an invader and has to leave, personally I do not agree,” a 65-year-old man told Glass. “The territory was ours, it was, that is the past. Now we are living together . . . We are made the same, there is no difference in race. We have to wake up, we have to become aware that our Mother Earth, which is not only the mother of the Kamëntšá, is the mother of the whole planet earth.”

In the roundhouse, transcendent visions

Perhaps the most vivid example of Glass’s immersion in his work was his experience with the shamanic yagé ceremony. This practice, he says, helped him envision the integral relationship between the potent hallucinogen, the Kamëntšá people, and the ancestral land they seek to recover and protect. Indeed, the Sibundoy Valley contains the greatest concentration of psychoactive plant species anywhere in the world, according to Glass, which could help explain the cultural importance that developed around shamans, long respected in the community as medicinal and spiritual guides.

Glass participated in four ceremonies—typically all-night affairs during which participants gather in a ceremonial maloca or roundhouse and drink yagé under the supervision of the shaman. The dark, viscous brew can be “disgustingly bitter,” he says, triggering violent waves of nausea in addition to powerful visions and feelings running the gamut from paranoia to euphoria. In field notes from one ceremony, he wrote in part:

Feeling sick, I went to the back of the veranda to be alone and to be close to the banister in case I needed to throw up. Then came the snakes, the visions, and the shakes . . . closed-eye visuals followed, predominantly serpentine in design. There were also the visions of death and decay accompanied by a feeling of generalized paranoia—omens of death lurking in the shadows of the maloca where the firelight didn’t reach. I did not feel well. Suddenly I sprang to the banister and vomited . . . then came a moment of total transformation by which visions of horror and an overwhelming sense of anxiety were replaced by ones of beauty and a totalizing feeling of love and amazement . . . It sounds stereotypical, but primarily I felt what could be described as a sense of universal unity and love . . . as I heard the shaman sing and the musicians play, I thought that at least in the realm of yagé ceremony, the Indigenous peoples here remain vibrant and proud.

Glass argues that the yagé experience validates Kamëntšá principles by generating feelings of love for others and for nature, and by reinforcing a belief in personal healing as a prerequisite for communal harmony.

“It was a unique and beautiful experience,” Glass says. “I felt privileged to share in an important cultural tradition dating back probably millennia.”

Research that was “personally transformative”

Glass’s prodigious research—his thesis stands at two hundred pages—has been supported by a half-dozen university departments and programs including the McNair Scholars Program and the Center for Undergraduate Research and Engagement. It was validated with a Humanities Undergraduate Research Fellowship and the awarding of exhibit space in the Knight Library; in one of the library’s so-called “tiny galleries,” he has created a multimedia display of belts, masks, and other crafts complete with interpretive panels and a soundtrack of Kamëntšá music accessible through a smartphone.

University mentors had high praise for Glass, whose work they likened to a graduate student’s—or better.

Reuben Zahler, associate professor of history, met Glass in fall 2021, when the latter reached out on the project. Typically, undergraduates seeking faculty help on independent research have dug no deeper on their topic than a Wikipedia entry, Zahler says; Glass had already visited the Kamëntšá people, developed a detailed premise for his thesis, and could articulate exactly what he sought from Zahler in guidance.

“He doesn’t want to screw around—he gets stuff done,” Zahler says. “Lots of folks in academia get lost in the theoretical. And in the business world there are a lot of people who are practical but not interested in thinking about anything bigger than their current project. Rowan is interested in both the abstract and in being very practical and organized—that is unusual even among highly successful professionals.”

The challenge for anthropologists is to allow your interpretations to emerge from the theories you’ve developed through the literature and whatever you are learning from direct field experience, says Maria Fernanda Escallón, assistant professor of anthropology and Glass’s thesis advisor. Glass has based his premises on what he’s learned among the Kamëntšá people, she adds, calling this “the key of good ethnographic research.”

“It’s like ‘detraining’ yourself a little bit so you can be attentive to what is being thrown at you,” Escallón says. “He has these beautiful ethnographic gems, these vignettes. He had the attentiveness—the moments when something is happening, somebody is saying something—it takes a real commitment to be really present and also connect it to what you’re writing. It’s mindful listening and being engaged to the world and making those connections. That is really beautiful.”

Glass graduates June 20 and will pursue a master of social and cultural anthropology at KU Leuven in Belgium this fall, with his sights set on a PhD. He’ll continue his work with the Kamëntšá people and is already planning his next visit. He hopes his research will help promote a better appreciation of the ways that Indigenous groups assert their rights and recreate their cultures.

From a personal perspective, Glass says, the project is already a success. As a first-generation college student, he encouraged other motivated undergraduate researchers with limited means to pursue similarly ambitious projects, calling his experience “personally transformative.”

“I grew up in the only Jewish family in a small, homogenous, conservative town in rural Oregon,” Glass says. “From as early as I can recall, I wanted to ‘escape.’ My desire to explore other cultures is, in part, an attempt to find a place for myself in the world. For all my wandering, there is something to be said for setting down roots in a place and coming to feel at home in it. The example of the Kamëntšá made me realize that perhaps this is possible for me, too.”

Matt Cooper is managing editor for Oregon Quarterly.